Part Two:

american geography

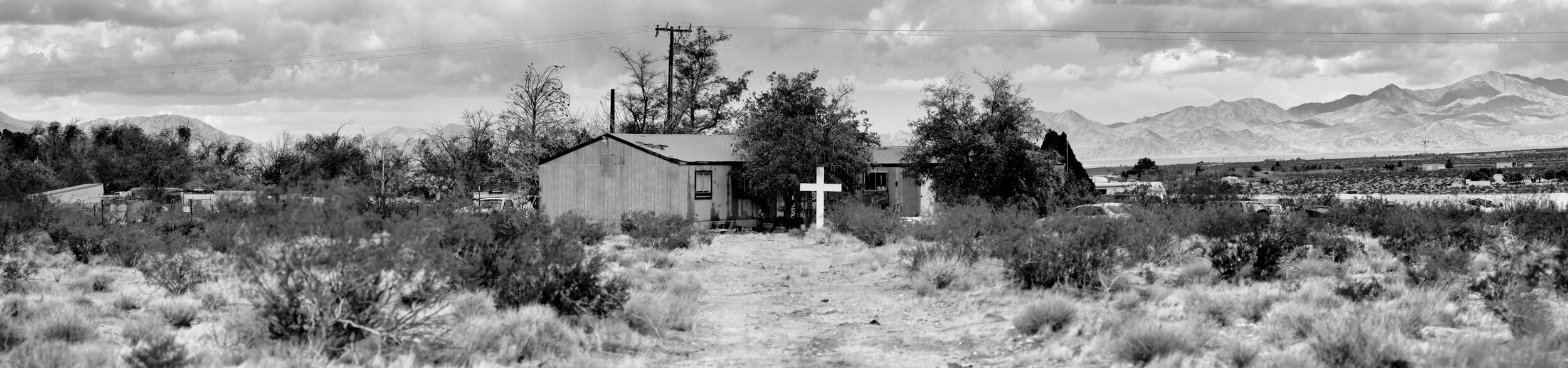

Between 2014 and 2020, photographer Matt Black traveled from his hometown in California's Central Valley to hundreds of other communities of high poverty across the United States. Concentrating on cities, towns, and counties with poverty rates above 20%, he discovered that he could travel from coast to coast without ever crossing above the poverty line. His exploration of this stark American reality grew to cover over 100,000 miles and 46 states, spread across five cross-country trips.

Cities Visited

Maps and Shadow Maps

The shadow map waits to be discovered, then reveals things that were not seen or understood. The shadow map unveils patterns and truths that contradict what we thought we knew.

TUESDAY, JUNE 4, 2019

Just how many places like mine are there in America? For the past five years, I’ve been traveling across the country trying to find out.

But much has changed in America since I began this work in 2014. My faith in my country, and in my own role, has been challenged.

Five years later, residents of Flint still have poisoned water, people are still sleeping under tarped roofs in Puerto Rico, and along the border, the suffering of immigrants has been turned into political theater, where people are looking at the same images but seeing two different things.

As I continue this work today, instead of uncovering remnants of a flawed past, it feels more like a foreshadowing of a far darker future. Instead of stitching together old wounds, these lines across the map seem more like veins just waiting to be opened.

Yet it’s too easy and too cynical to say that all is lost, that previous faith was misplaced, that truth doesn’t exist, and that common ground cannot be found. But my mind is unsettled, and these questions remain far from answered. I will attempt to understand these questions, this country, and these times in the only way I know how: to go look and see.

TUESDAY, JANUARY 5, 2016 FRESNO, CALIFORNIA

Leaving home. I once told myself that all I needed to understand was my corner of the world, but I've been crisscrossing the country for a year now, and all I want to do is see more.

I’m catching the 11:00 p.m. bus from Fresno to Calexico, 438 miles, 10 hours. One backpack with one pair of pants, one long-sleeved shirt, one T-shirt, jacket, hat, four pairs of socks. Panasonic camera, XPan camera, six lenses, 30 rolls of film. From Calexico, I’ll take the bus cross-country, to Bangor, Maine, and back. It’s 3,317 miles, one way. About six weeks.

The waiting room is largely empty, mostly women sitting with their bags: a young woman with long hair and a cell phone; a middle-aged woman in a black zippered jacket; an old woman with glasses.

The bus is white, unmarked, and there are 10 passengers, including me. The driver announces the rules: no smoking, no cussing, no music. A passenger replies: “God bless you.” South on Highway 99, we pass through Tulare, Delano, Bakersfield, and arrive in Los Angeles at 3:40 a.m. The highway off-ramp is lined with shanties. City Hall is so brightly lit, it spills a white haze across the empty downtown and fills the dampened bus windows with a gauzy shimmer.

The sun rises in the town of Indio as the bus picks up a young family with two egg crates tied with twine for luggage. We arrive in Calexico two hours late. I walk three blocks to the Border Hotel, on 4th Street, a low-slung building with a tile roof and bars on the windows, and pay my $50 plus $10 key deposit, cash. While I fill out the form, the clerk tells me three times that I am the only one allowed in the room. The last time, for emphasis, he says if he sees anyone else in my room, he’ll keep the deposit and kick me out.

It's the first night of another long journey.

TUESDAY, AUGUST 13, 2019 TUBA CITY, ARIZONA

I talk with Jeremiah, Jacob’s brother, who sells blood to make ends meet. “The first five times you go in, they give you $50 per visit. Then on the sixth, and on forward, they give you a twice-a-week schedule to get your plasma. The first out of that twice a week is $25, and the second one is $35. So it’s set up like that for me now. I hitchhike down there and get cash back. It’s a source of income, you know, and sometimes I use that to pay for our water, for propane, stuff we need around the house, paper towels, necessities. But you’re weak sometimes.”

---------------

FRIDAY, JANUARY 15, 2016, TULSA, OKLAHOMA

A long line waits in front of the bus, engine shut off but with its door wide open. The bus is scheduled to depart at 5:00 p.m., but the driver doesn’t appear until 5:15. At the front of the line, an older woman pays her fare in nickels and dimes as we all wait.

I take my seat and watch billboards pass downtown: This Land Is Your Land; Affordable Bail Bonds; Ringgold Bail Bonds; Davis Bail Bonds; Amigo Bail Bonds.

Saturday, January 16, 2016

Tulsa, Oklahoma

12:44 p.m.: Arrive Tulsa Greyhound Depot, 300 block Detroit Ave, 1,179 miles to Harrisburg, PA. Ticket: $185.50

A man is dumpster diving in a trash can by the door. He pulls out something that appears to be a slice of pie.

1:59 p.m.: Bus departs

5:05 p.m.: Arrive Springfield, MO. The Queen City of the Ozarks.

$1.30 small bag nacho Doritos, $2.50 20 oz Aquafina water. $1.00 vending machine coffee, small with sugar, option A4.

6:17 p.m.: Depart Springfield, MO

7:04 p.m.: Arrive Lebanon, MO

7:50 p.m.: Arrive Saint Robert, MO

8:19 p.m.: Arrive Rolla, MO

Dinner: cheeseburger, fries, Coke $10.43

8:39 p.m.: Depart Rolla, MO

10:32 p.m.: Arrive St Louis, MO

Two black coffees with sugar, $2.19.

12:06 a.m.: Depart St Louis, MO

12:14 a.m.: Cross Mississippi River

1:50 a.m.: Arrive Effingham, IL

5:17 a.m.: Arrive Indianapolis, IN

Breakfast: 7-inch pizza, $6.20; Medium bottle of water, $2.09; Coffee, $1.09; Tax, 92¢; Total, $11.10.

6:27 a.m.: The bus has a flat tire.

7:00 a.m.: Starts to snow.

8:34 a.m.: Depart Indianapolis, IN

9:48 a.m.: Crossed border into Ohio.

10:17 a.m.: Arrive Dayton, OH

11:50 a.m.: Arrive Columbus, OH

Lunch: cheesesteak sandwich, coffee, $8.08.

12:21 p.m.: Depart Columbus, OH

1:18 p.m.: Arrive Zanesville, OH

1:52 p.m.: Arrive Cambridge, OH

3:50 p.m.: Arrive Pittsburgh, PA

4:29 p.m.: Depart Pittsburgh, PA

7:10 p.m.: Arrive Hustontown, PA

Coffee, $2.18.

7:17 p.m.: Depart rest stop

8:24 p.m.: Arrive Harrisburg, PA

GEOGRAPHY

RIO GRANDE VALLEY (2015)

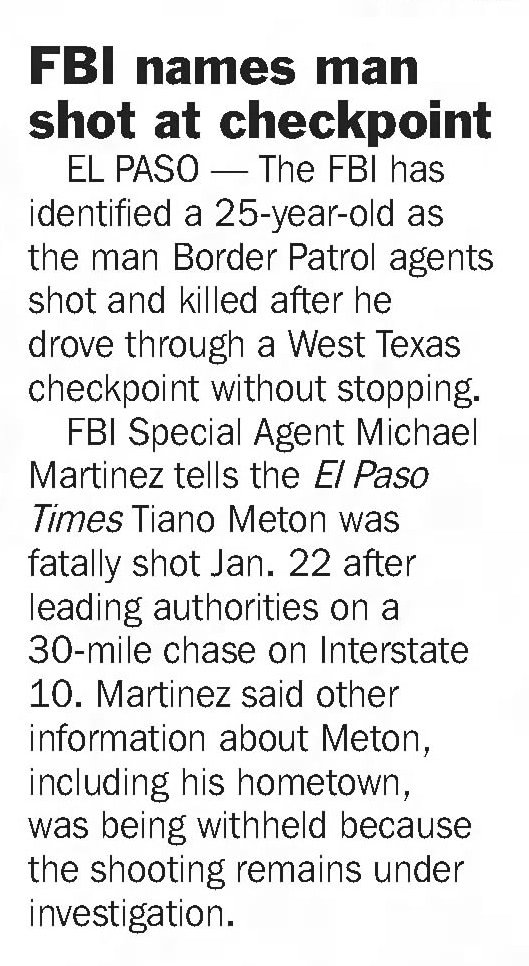

The Rio Grande Valley in Texas lies at the southeast end of the state, abutting Mexico, and covers 4,244 square miles and four counties. Each year, thousands of people from Mexico and Central America brave risky trips, often on foot, to enter the U.S. for work. The International Organization for Migration reports that in 2019, 73 people died while trying to cross the border. In 2020, 113 people died. From January 1 - August 28, 2021, the death toll was 298.

Falfurrias, Texas, June 17, 2015

Eduardo Canales: “El Proyecto Desaparecidos, it’s a missing migrants network, Derechos Humanos, No More Deaths, and the South Texas Human Rights Center collaborate on Missing Persons reports and search and recovery, search and rescue as best as we can.

This is a name of a person that just came through: his name is Moises Abram Oriana Leon. His date of birth — well, he’s approximately 36 to 38 years old, from El Salvador, and one of the friends of the family’s called the person Moises has been calling in while he was on his trek. And this is already in the United States, in the state of Texas, between Highway 77 and 281. He started in McAllen and walked directly north, between those two highways, Highway 77 and 281.

After a few days, he was lost and separated from his group. He is with one other woman, no information on her. His leg is injured, and he has been throwing up.

On the morning of [June] 15, that’s two days ago, on Monday, he described a gas drilling station with a lease number and plate on the fence. Plate on the fence, Abaco Operating License number Ball 17280, Acre number ID 220447, lease number and gas tank, Ball Gas, lease number 220447.

Internet searches — and I believe No More Deaths did that — internet searches on this lease number lead to GPS coordinates of 26 degrees, 854628, minus 97 degrees, 936328. His friends spoke to him on the phone while he was at this location and confirmed placement of structures from Google Earth.

After being at this location, he tried to walk directly east for two hours. He wasn’t able to cover much ground due to his injuries. Where he is now is by a pond, and he can see cattle. His last phone call was at 12:30 PM on [June] 15, that would’ve been Monday noon, a little after noon. He said he had tried to call 911, but the call had dropped. He was going to try again when he hung up, but his phone battery was very low. “

SATURDAY, APRIL 13, 2019 INDIANOLA, MISSISSIPPI

I drive up Highway 49 to Drew, where there’s a food handout today. Four hundred people show up. The high school was shut down two years ago, but some classrooms are used to distribute commodity food. Today, for a single person, it’s a brown paper bag with potatoes, apples, frozen meat; for a family, a cardboard box with the same, just more.

Almost half of the students in Drew drop out. On a whiteboard in a classroom, there’s a handwritten list of reasons to quit: Want to be cool; Teachers allow breaking of rules; Too many suspensions; Not prepared academically; Transportation; No future plans; Think it’s hard; Tired of rules; Financial; Pregnancy; Fear of failure; No babysitter.

Geography

Martin County, Kentucky (2019)

In his 1964 State of the Union address, U.S. President Lyndon Johnson announced his “war on poverty.” Famously, Johnson also spoke to Americans that year from the front porch of unemployed Martin County, KY, resident Tom Fletcher, who enumerated for the President the problems of living in poverty — a plight suffered by one in five Americans at the time. Johnson’s legislation included such cornerstone programs as food stamps, Head Start, Medicaid, and Medicare, and lifted thousands out of poverty.

But 55 years later, the “war on poverty” seems to have ground to a halt. In Martin County — population 12,929 — the poverty rate is 34.4%. Many households once sustained by coal mining lost jobs, as the industry dwindled and was plagued by issues such as the massive, Massey Energy-owned slurry impoundment spill in 2010 that poisoned two creeks and the Tug River. In 2017, fewer than 300 miners worked in Martin County, while more than 25 boil-water notices were issued to residents whose drinking water is contaminated, drawn from rivers and streams that also serve as unofficial wastewater dumping grounds.

WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2019 INEZ, KENTUCKY

Harold lives in a faded, orange-painted house on Old Route 3 down the road from the county seat. On his family’s front porch in 1964, President Lyndon Johnson announced his War on Poverty. “Our objective: Total Victory,” Johnson said.

Except for the orange paint, the house looks the same as it did in the pictures that day: cinder block steps, tin roof, cellophane tacked over the windows, a barometer next to the front door. Two recliners and an old couch sit on the warped front porch, next to a card table on which are three packets of flavored cigars, two buckets -- one full and one half full of empty cans -- and a stack of firewood. Inside, in the little cramped rooms, there is a picture of Jesus hanging on the wall next to the front door, a coal-burning stove for heat, a white plastic basin for washing dishes with a can of Comet cleanser on top. The linoleum floor is peeling, held down by thumbtacks in the corners.

Harold sits on the porch, wearing black jeans, a bright blue T-shirt, hiking boots. Of Johnson, he tells me, “He lied, just like everyone in the past lied to us.”

---------------

WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2019 LOVELY, KENTUCKY

It’s cold, and there’s snow on the ground. Samantha and Derek are in their camper. Its broken-out windows are covered with plywood. They ran a burner on the cookstove all night long, so it is warm inside, but the plumbing beneath the trailer has frozen, so they have no water.

Samantha is pregnant and has battled several stomach infections. She was prescribed two antibiotics but can’t afford to fill the prescriptions. She hasn’t eaten in four days, has no health insurance, and can’t see a doctor again unless she returns to the emergency room. She spent her last nine dollars getting a ride home from the hospital.

---------------

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 2019 INEZ, KENTUCKY

Larry lives alone in a wooden house whose slumping walls are decorated with dozens of faded family photos. Reed-thin, with a bald head, and a clean-shaven face resembling Eisenhower, he wears blue jeans, a faded T-shirt, and a heavy canvas jacket. A pair of calf-high work boots sits next to his easy chair, their untied laces spilling across the floor. Larry has throat cancer and two years ago had part of his larynx removed. Now he speaks in a thin, raspy voice and is difficult to understand sometimes.

The pump on his well went out two months ago, and he has lived without running water since. He collects rainwater from a downspout connected to his roof and keeps it in a five-gallon, white plastic barrel next to his front door, washing up there before he goes to town. He receives $800 a month in Social Security. No food stamps. No benefits from the Army for his service in Vietnam. He cooks with a single hot plate: “People living under bridges have it better than me,” he says.

Today it’s icy and cold, and he has run out of firewood. He has chopped up a wooden window frame from a pile of scrap lumber to burn in his little, cast-iron wood stove. The bent stove-pipe is so old and worn out that it’s almost transparent, the licking flames glowing visibly through the thin metal from the wood below. There are two clocks in his living room. One is red and shaped like an apple, one is black and white striped like a zebra. They tick the seconds away on a slightly offset rhythm, their echoing call and response filling in the silent gaps of conversation.

Martin County, Kentucky (2019)

“The powers that be are still working under the idea of the trickle-down effect. Every place where they put money, they say it’s going to help poor people by doing this, but there’s no trickle-down at all. As a matter of fact, there’s a siphoning up. Because when we should have gotten help with the water plant that was dilapidated, back in 2000, instead they’ve been putting it into mountaintop removal sites, to prove that they did the right thing by removing the mountain. And now what we’re having to do, the last money we’re getting is to pump water up to a removal site where they destroyed the waterways to mine coal. We’re all fighting our little fires, and we’re not realizing that the fire is coming from above and it’s raining down on us.”

“Turning a blind eye on this, and not just here but the whole infrastructure of our nation, turning a blind eye is not getting us anywhere. They cannot fix half of what our problem is and it still be okay. If your roof’s leaking and you repair half of it, you’ve still got a leaky roof going into your house… Over 50% of the county lives on a fixed income, social security $700 a month. If you pay your rent, and your water, and your electric, your money’s gone; so what do you do all month? We have to keep buying bottled water; how are you going to do that? What’s the difference between that and a third-world country? Here is a lot worse than most places. And because we’re poor and isolated in the Appalachia mountains, nobody knows how bad it really is.”

“Sometimes the water smells like bleach a lot, and sometimes it smells fishy. It don’t smell good at all. I don’t drink it. And everybody else here won’t drink it, there’s six of us that live here and nobody drinks it. [We] buy bottled water, or just don’t buy none at all, have to use tap. We’re a little county, we just get pushed under the rug. There’s people around here, kids go to bed hungry, they live with no electric, no water, it’s here every day. The kids go to school, that’s the only time they get milk. You don’t see no Food Bank here, or nothing like that — you go once a month to the Reach Out and get a box of food, that’s it. People are on a fixed income. You don’t get a lot of food stamps. We have six here; we only get $500 a month in food stamps, and when there’s only $900 in money and $500 in food stamps, it’s not enough. That’s $350 a month rent, $200 electric, water, garbage, and how can you afford to feed kids? It’s hard. I’ve seen kids go to school dirty because apparently, they didn’t have no water.”

“It’s hard when your kid says, ‘Dad, I need to take a shower.’ What kind of man do you feel like? You feel like nothing, you can’t even let your kid take a bath unless you go to a friend’s house. Those blue six-gallon jugs, we’d have to bring home just to water our dogs. We went a month and a half, two months, without water. When you was growing up, the people would try to help everyone. That ain’t true any more. School’s starting, [the kids]’re looking at you with big eyes: ‘How am I going to take a bath? How am I going to wash school clothes?’ They’re making money hand over fist, and they don’t realize the little man. They’re all about theirselves. You can go around telling me ‘I got kids, blah blah,’ they say, ‘Ain’t our fault.’”

Only in America

Can a guy from anywhere

Go to sleep a pauper and wake up a millionaire

Only in America

Can a kid without a cent

Get a break and maybe grow up to be President

Only in America

Land of opportunity, yeah

Would a classy girl like you fall for a poor boy like me

Only in America

Can a kid who's washin' cars

Take a giant step and reach right up and touch the stars

Only in America

Could a dream like this come true

Could a guy like me start with nothing and end up with you

Only in America

Land of opportunity, yeah

Would a classy girl like you fall for a poor boy like me

Only in America (poor boy like me)

Only in America (only in America)

Only in America (only in America)

Only in America (only in America)

Only in America (only in America)

"Only in America"

Jay and the Americans, 1963

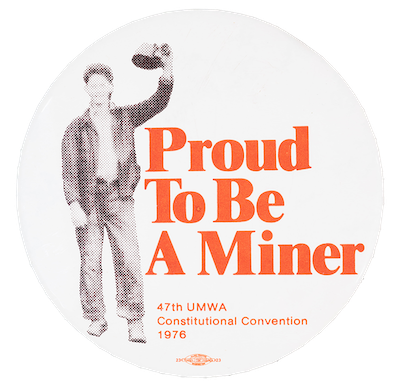

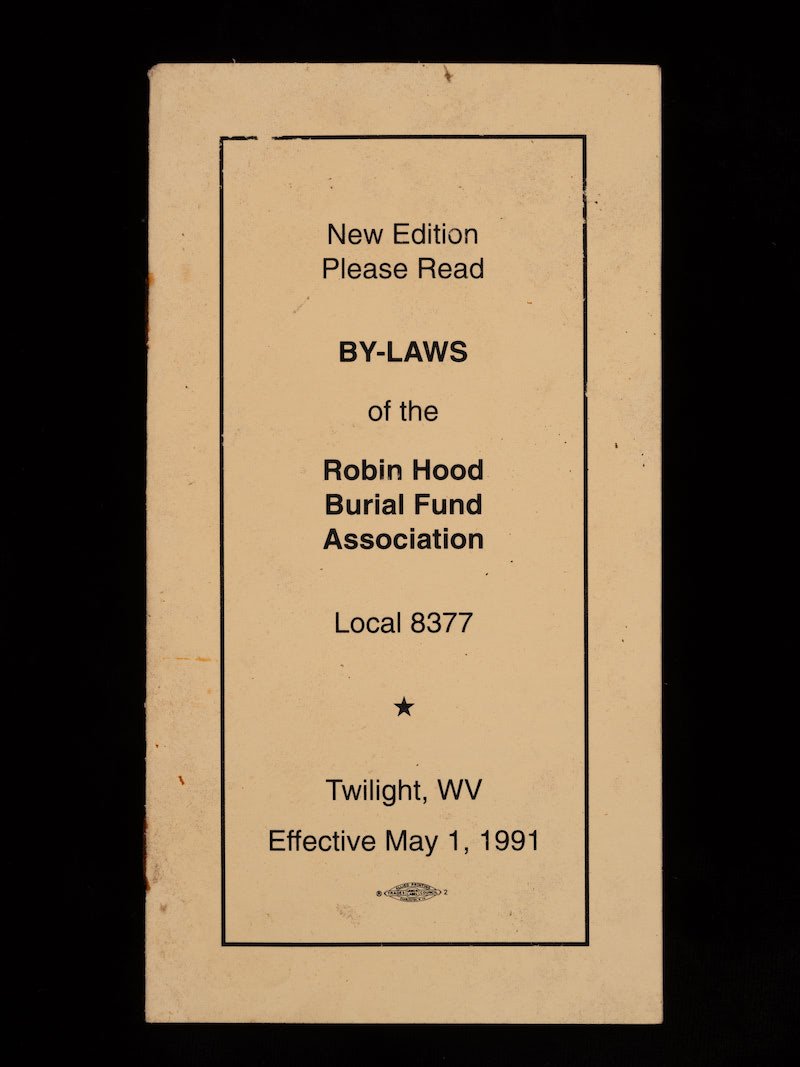

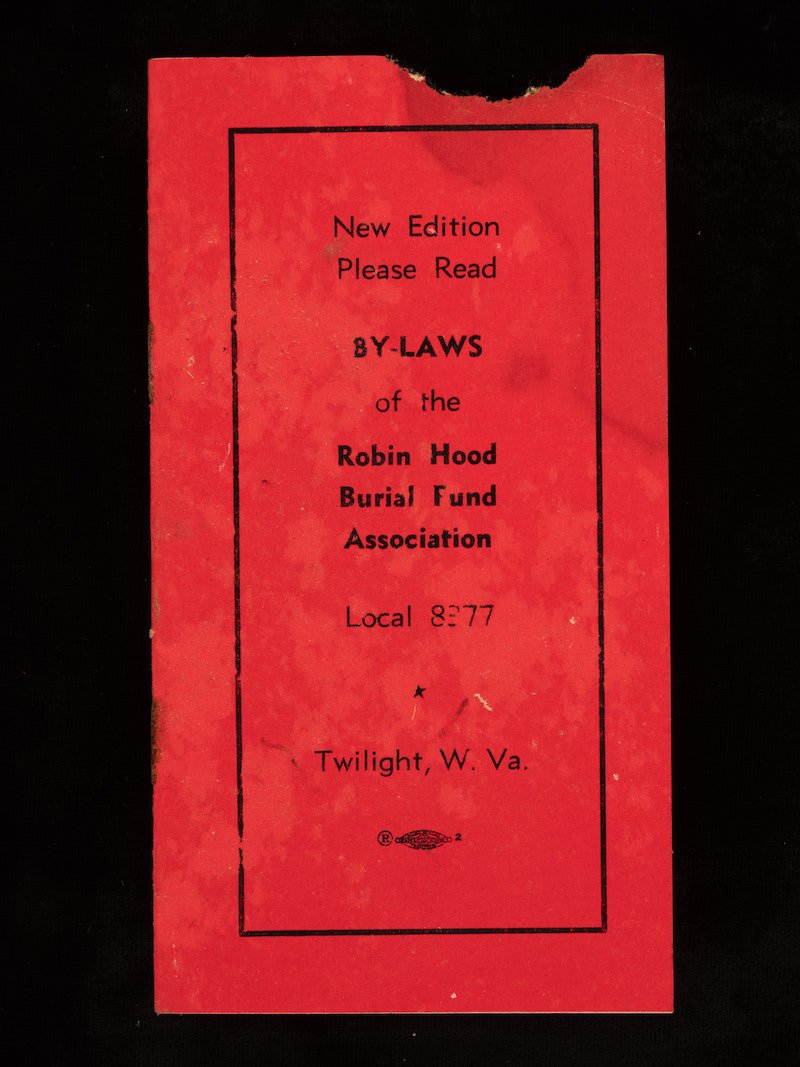

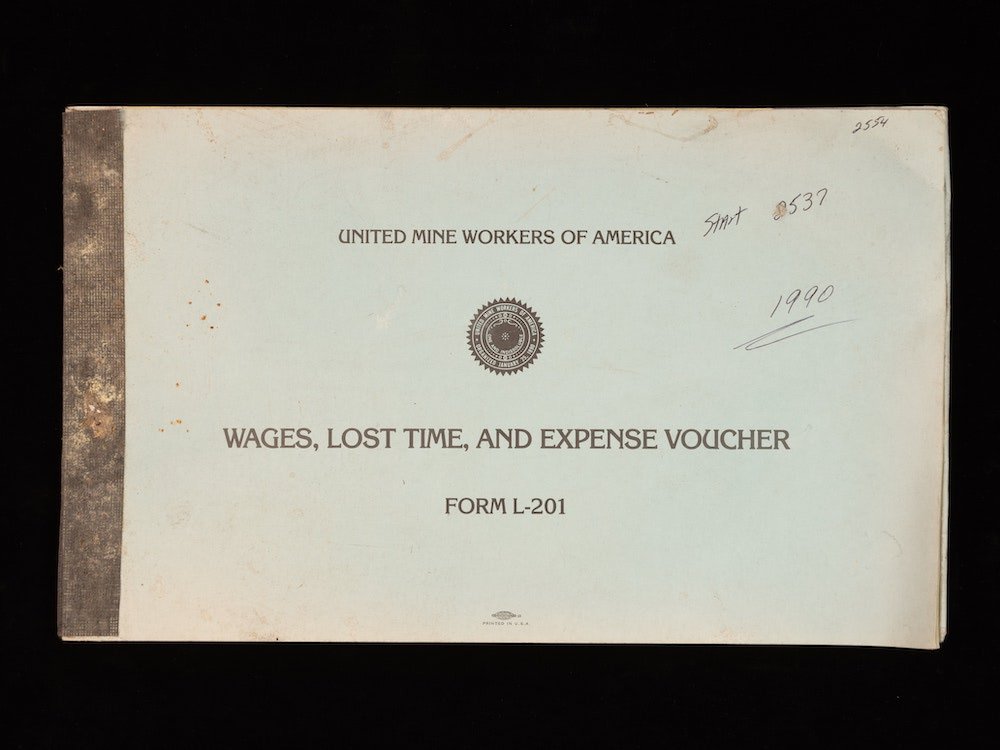

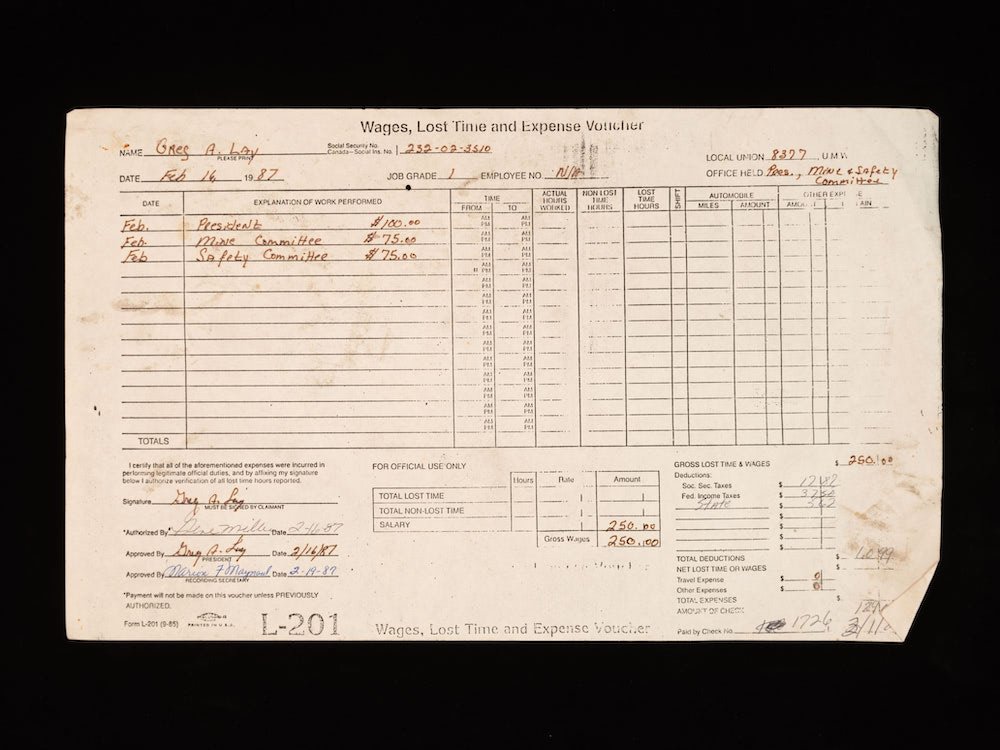

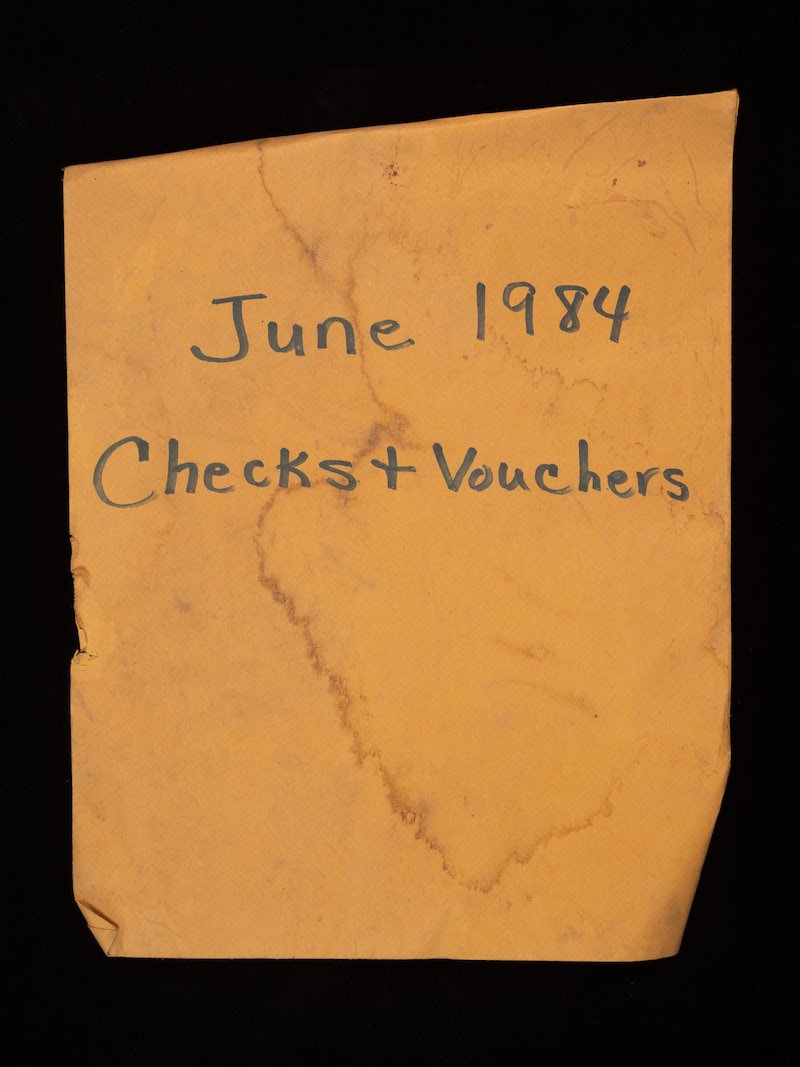

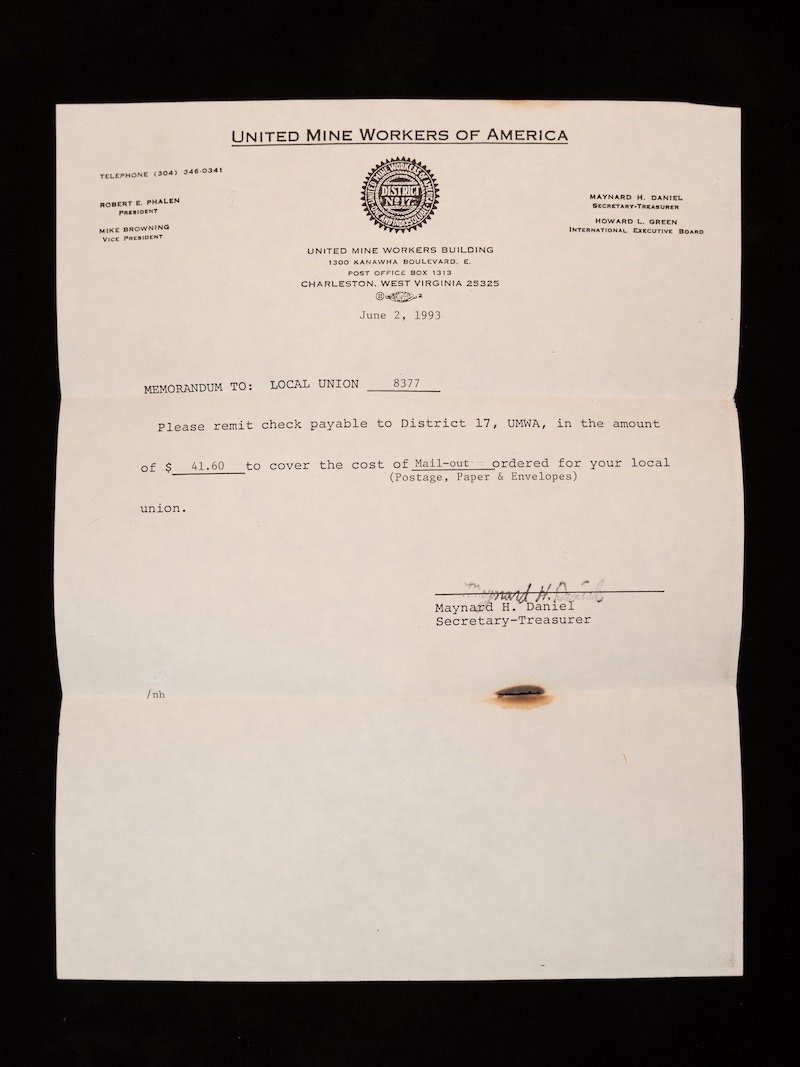

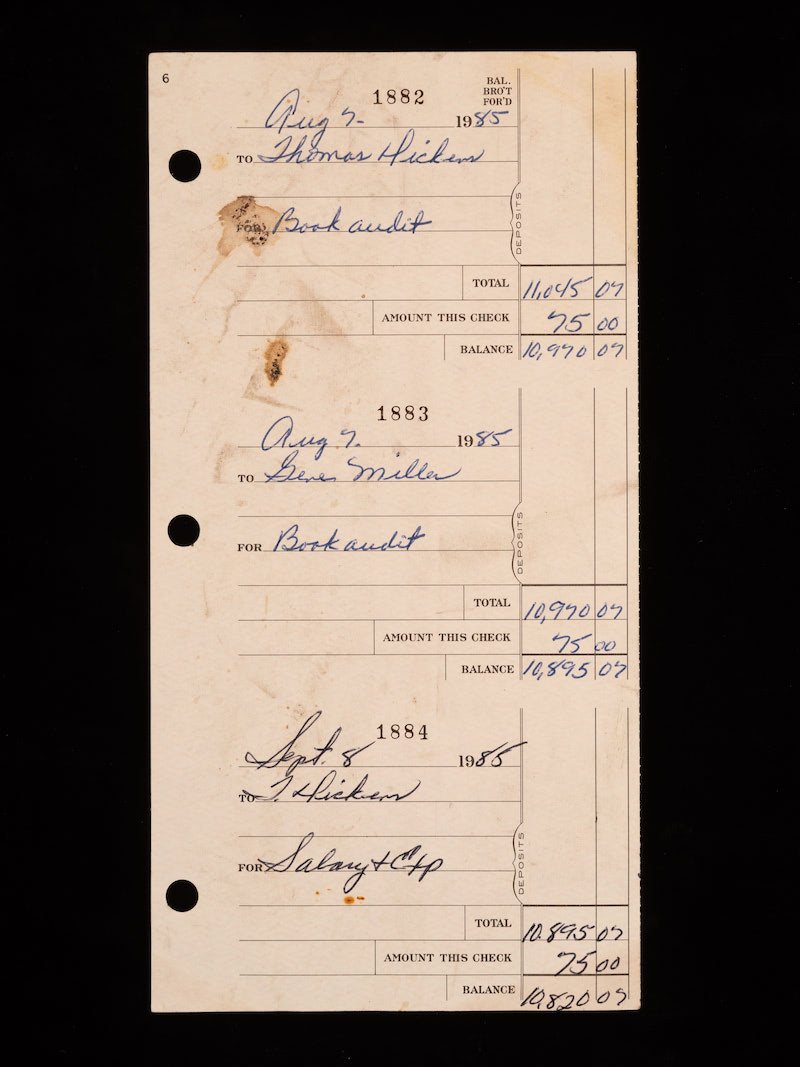

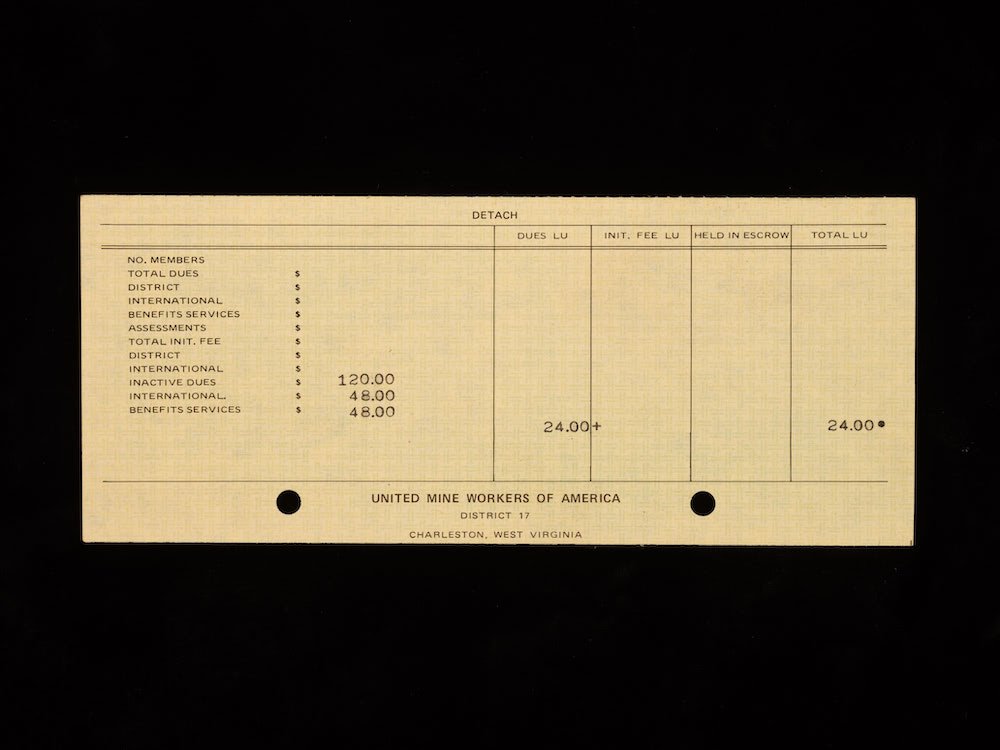

UMWA Local 8377

Twilight, West Virginia

0 members, 0 assets, 0 employees

Found documents from an abandoned church chronicle the end of a branch of the United Mine Workers of America, when mountaintop removal hollowed out a mountain community.

American Geography

Fred Ritchin: July 2021

In this “age of image,” one might think that everything of importance has been rendered visible. In fact, the profusion of imagery that surrounds us serves largely to distract from that which actually exists.

“What I was doing was not a portrait of marginalized America,” Matt Black asserts in a recent interview about ‘American Geography’ that I did with him, “but a portrait of America itself. And the point that needed to be made was how much this is a part of American life, not something on its edges.” Rather than buying into the prevailing myth of the United States as a country of limitless opportunities where nearly anyone can pull themselves up by their bootstraps, Black views an enormous portion of its people as hemmed in and frustrated by a lack of adequate social services so that “your future is determined largely by where you are born.”

As a result, millions of people lack adequate education, health care, clean water, food, and housing. They end up blaming themselves for their difficulties, and are blamed by others, rather than holding the institutions responsible that have thwarted them. “I’ve tried to deal with the psychology of powerlessness, and how these things influence people’s thinking about themselves, and about their communities. And it is something I think is underestimated,” says Black.

His own upbringing informed his thinking. “People tend to focus on the bright and shiny parts of the country, but not the parts that are intimately connected to that prosperity but don’t share in it,” Black asserts. “For instance, where I live in the Central Valley, this area produces a quarter of the food in the United States, but enjoys very little of the benefit. It’s still one of the poorest areas of the country.” Instead of being supportive, he finds that the government can seem “to be motivated, not by caring, but by spite.”

The photographs that Black has produced makes visible vast, geographically disparate regions of the country overlapping in their marginalization. “These hierarchies of power are what the work is exploring, who gets what and when and where, and who gets to say what America is. And that’s what I’m talking about. America from the ground level is very different.”

As I write this, I have read about a rare strike by workers in the Frito-Lay plant in Topeka, Kansas, owned by the food and beverage conglomerate PepsiCo which generated more than $70 billion in net revenue in 2020. At the plant in Topeka, they produce popular snacks such as Fritos, Cheetos, Doritos, and Tostitos. “Workers have publicly aired a list of grievances ranging from stagnant wages, high turnover rates and a lack of hazard pay during the pandemic to 84-hour workweeks, warehouses in triple-digit heat with no air conditioning, months on end without a day off, and so-called ‘suicide shifts’ where workers are only off the clock for eight hours before having to come back in,” The Guardian reports. “In an interview with ‘Vice,’ Mark McCarter, a 59-year-old palletizer and union steward who has been working at the facility since he was 19, described one instance a few years ago where a co-worker died on the line and the company had his body moved to the side without stopping production.”

In an open letter to her employer, another worker wrote, “Your negotiator told us that it isn’t that Frito-Lay can’t afford to give us raises, it’s that he is there to protect the stockholder investments.” And who are these stockholders? A recent article entitled “Who Owns Stocks in America? Mostly, It’s the Wealthy and White,” reports that “Families in the top 10% of incomes held 70% of the value of all stocks in 2019, with a median portfolio of $432,000. The bottom 60% of earners held only 7% of stocks by value.”

This is Matt Black’s point, exactly.

Conversation (October 2020)

Fred Ritchin: When I knew this project, it was called “The Geography of Poverty,” and you changed the name. And could you explain why?

Matt Black: It was a feeling I had for a while. What I was doing was not a portrait of marginalized America, but a portrait of America itself. And that the point that needed to be made was how much this is a part of American life, not something on the edges.

But do you think you're dealing now with the mainstream of America, with this center of America? How would you define it?

What I'm getting at is at the center of the American experience. And people tend to focus on the bright and shiny parts of the country, but not the parts that are intimately connected to that prosperity but don’t share in it. For instance, where I live in the Central Valley, this area produces a quarter of the food in the United States, but enjoys very little of the benefit. It's still one of the poorest areas of the country.

So I guess you're also saying they're overlooked, when media does coverages and so on, it is on the bright and shiny, or it's on the extremes of violence or protests or whatever it would be, but the people who actually do the work, and provide, as you said the food for the country and so on are overlooked.

Exactly my point.

So you're not seeing any social mobility then, the big American Dream, Horatio Alger, and all that was that this is a country where it could pick you up by your bootstraps, and do what's needed to get an education, skill sets, and move on up. You're not seeing that?

Not seeing that. Seeing the opposite of that. That your future is determined largely by where you are born.

And is there anything else in there? It is a gender issue, a race issue, ethnic issue, religious issue? Is it just the geography, or is it something else, part of that equation?

I mean, part of the way I'm feeling about this work and particularly in the context that we're in right now is I feel what needs to be made are universal statements. And that's what I've attempted to do here in this work, is to understand people united by this framework, living in areas that you don’t normally see put together in one body of work. Within that broad grouping there's many different issues, many different identities, and many different things going on. But what we're seeing is now is how these differences have been harnessed to divide. That's completely contrary to where I'm coming from.

Here in New York right now, there's all these kinds of conversations which are based not so much on geography, but are based upon issues of race and sexual orientation, religion, as reasons why people are particularly brutalized, why people are discriminated against, why people bear burdens that other people don't bear. And the reference is not to a particular place necessarily; the reference is to the inevitability of a diminished life potential, because one is, for example, born black as opposed to white. But what you're talking about seems to be something that's very much like a social economic infrastructure, which involves everybody who's born in that place. That even if you're born Protestant or Catholic, or white or black or whatever you might be born, you're still going to have enormous difficulties trying to extricate yourself from it or have any sense of self or self-worth. Is that an accurate-

Yes, that is precisely how I feel. And that's something that's just borne out by experience. None of this is to diminish those critiques, which of course are true and need to be done, but the broadening of those critiques, which I also think needs to happen. Place is important. It is another mechanism by which social power gets expressed in America.

So in your ideal vision then, the rest of us would be informed as to what's going on in many geographies, in many parts of the country; we would take notice of it. Laws would be passed and so on, so that the benefits would be distributed more equally, so that there'd be more attention, more respect, for these other areas.

Yes, but first of all, we have to recognize what America is, and who gets to define what America is. These hierarchies of power are what the work is exploring, who gets what and when and where, and who gets to say what America is. And that's what I'm talking about. America from the ground level is very different.

How do you compare this to, let's say the 1930s, the FSA, the attempts by the government to be supportive of groups of people who normally didn't have a safety blanket? Are you seeing pretty much the opposite at this point? That the government is not being supportive and the people are being overlooked, as opposed to the 1930s where we were actually using photography to look at people and to take them into account.

It is exactly the opposite, and on the part of the current government it seems to be motivated, not by caring, but by spite. If you pay attention to food stamps and other supports like that across the country, they're being slashed to the point of almost irrelevancy, zero. And it's being done with a sense of punishment and spite.

So how do those poor respond to this? Do they think it's with anger themselves, with bitterness, with a sense of being resigned, how do they respond?

I've tried to deal with in the work the psychology of powerlessness, and what these things, how they influence people's thinking about themselves, and about their communities. And it is something I think is underestimated. In the end, these things are not just about finances.

Which they feel it's their fault somehow.

Exactly. And that's why talking about these things is so fraught, and so complicated in America because we still accept these “bootstrap” ideas as being valid, when all experience is to the contrary. But people still accept these mythologies, “the land of opportunity” and so on.

So what motivated you to make this hundred-thousand-mile journey?

I don't know if you know that much about me or where I'm coming from, but just to step back for a second, my goal for many years as a photographer was to focus on my place, to use my work to be a voice for this place. And when I first started this project, the focus again was on this part of California and trying to take a different, more of a step-back look. I did that for about a year.

But then what happened with the work and also with myself is I felt like I had 20 years of working here in California, but when I would work on ideas here, I always had in mind the universal. To me, it was obvious the connections, it was obvious that we're all connected, but I found that few people were willing to make that leap with me. It almost becomes a self-defeating thing. Because to say, okay, for example, “in the Central Valley of California or in rural Mississippi, these stories exist” -- by doing it that way, it makes it easier to ignore. Like saying, “Keep it over there, somewhere far away from us.” So, the idea was to try to bring it as close as possible to show how universal it is in this country, these sorts of experiences.

Also I'm trying to grab at something else that I think is really important. Coming back to the Central Valley, it's essentially a colony, an interior colony of America. It's an extractive thing. It's not included in this American story that's been written elsewhere. It just feeds the raw materials for that American story to unfold. For me growing up, it was a sense that “the place I'm from is not part of what I see on TV.” And there's a built-in sense of disempowerment that goes with that. Anyone who's from a place like this knows the feeling very well. I tried to harness and internalize that feeling as much as possible, the tragedy and disillusionment that goes along with that. I used that to inform the pictures.

How big is that America that you're talking about? What percentage of the country in your mind do you see it as?

This is the country. It is. If you go and look on the ground level, this is America.

And they'd been left out of not only TV and movies and newspapers and magazines and so on, but they've been left out of government policies or support networks, or the chance for higher education, of skill training, the whole thing?

Clean water, clean air, health care, life expectancy -- just go straight down the list, any which way possible that injustice can be manifested, it's there.

Do you feel that the impact of Lange’s “Migrant Mother” could be replicated today in any way? Do you think that image, your images, anybody else's images could focus the country, or do you think we're in a different place now?

Yes, I think they can. I mean, and I think they continue to. The hard part about trying to identify those pictures is we don't have the benefit of retrospect. I don't think we're going to know what those images are until later. But I still believe that photography has the ability to crystallize thought and emotion, and to motivate people to think and connect with each other. If I didn't believe that, I couldn't be doing this.

But do you think it works better on the local level, nationally, internationally? I'm not seeing that many iconic images. We are going through a massive depression, a pandemic, but I don't see the equivalent of the Dorothea Lange images, an icon to focus. Yes, I agree with you that there many images have impact, but I'm trying to get at is it a series of images that make a difference now? How does it work differently? Does Facebook do it better than The New York Times used to do it? What's your opinion?

Yeah, I mean, photography has changed. It's much more common. And I think you're right, now it's more about a sustained engagement than about the individual image. And maybe that's good, maybe an individual image can simplify things too much, but I still think despite that, despite the fact that we're just kind of awash in images, photography still can and does perform that function. It communicates on a human level and an emotional level. I don't think that ability has changed at all.

Okay, now let's switch to something else, which is your printing. You have a very distinctive quality of print that you make. You're also working in black-and-white. And what are you trying to get at with the print? They're very dramatic images the way you make them and so on. What's your intention in the printing and the choice of black and white?

The pictures look to me how pictures should look. And I can go into a little bit of detail of what it's like to photograph in an environment like here in the Central Valley, and that it's very difficult to get a full-range image in a place that is so saturated with sun. When I learned photography, it was all in black and white, and to get a full range image, you had to push your film in order to get a black and a white. You had to use contrasty film or everything just came out grey. And since then I've never really changed or questioned it. To me, that's just how photographs look.

It's funny, David Goldblatt said pretty much the same thing as you. Living in South Africa, they asked him, why don't you have light like the Europeans? And he said, the light here is completely different, that it's never going to look like them. So that's what you grow up in, that's what you see.

Interesting. Yes, that’s it. And to press that idea further, there’s a lot tied up with what you grow up in, that’s what you see. It’s a part of you, it’s how you see things. It’s what makes your work distinctive, and you can hone it but not make it up from scratch, and every photographer has to find it for themselves and then explore it as fully as possible because that’s what they have.

Just to get a little deeper in this, you grew up in the Central Valley, you're still in the Central Valley. Is the choice because of culture, because you really like it there? Is the choice because of family, friends, because you're familiar? What went into the choice to... you're very loyal to it, you remain there. A lot of people don't. A lot of people move away, especially from areas that have their share of hardships as the Central Valley does. So what's your thinking there?

Well, first of all, it's home and yes, family is here. And then secondly, a degree of commitment, feeling like I have an obligation to continue to work here. And then third, it gives me the proper perspective. It would be hard to maintain my own clarity without being here. So it's all three of those things together, equally weighted.

So you're feeling then, as the insider because there's an authenticity for you in remaining in the Central Valley and growing up there and being the inside guy, you see things differently than an outsider would, I'm assuming.

Well, I think the insider/outsider thing is really complicated. I think the moment you pick up a camera, you are automatically outside the situation you're in. So I don't presume to adopt any sort of personal morality out of what I'm talking about. What I mean is for me personally, to maintain my clarity of thought, it just serves me better to be here.

How do you know when you're doing the right thing? This is part of what I was asking about your working method, do you talk with the people? You wouldn't make an image of somebody you just passed on the street standing in front of something. You'll talk to people.

Absolutely. A big part of this project has been interviewing people and getting their voices and stories. I would never make an image that I felt was going to harm somebody.

Okay, and how would you define doing harm to people with photos? What does that mean?

To me, it’s important that you're taking an image that is truthful and not denigrating. An earned image that’s fair. This project has been two very different ways of working, sandwiched into one body of work. One is walking the spaces, walking the streets, cities, and towns, just observing and making images like that. The other has been the series of very focused stories where I'm working much more as a traditional photojournalist, which my own personal history and background is more aligned with. For example, I just finished a big project about drinking water across the US, a half-dozen or so different areas across the country connected with contamination and access to clean drinking water; other stories, going to Puerto Rico after the hurricane, the run-up to Standing Rock, Flint. Spending time with people, working in a much slower fashion. It's very much a collaborative journalistic enterprise when I'm doing those.

Explain collaborative, collaborate with the subject, with the writer?

Collaborative in terms of communicating a story. For instance, when you're photographing contaminated drinking water, you're going into people's houses and you're seeing bathrooms and how people interact with water in all these different ways. Mothers trying to give their children baths by pouring in little tiny bottles of drinking water. So it's collaborative in terms of agreeing this is something that should be documented. And respecting the ability of the camera to change things.

Let's talk about text a little bit, because it's outside the frame as a way of contextualizing, as a way of doing it. So you have a lot of these kind of diary segments, meeting people, what it was like, what you felt. Is your intention to contextualize with what we're just talking about, here's somebody without drinking water. And the text then says “X percent of Americans don't have drinking water.” Do you think of it that way, or is it a more lyrical approach without those kinds of overarching statistics and so on?

My feeling about both the photographs and the text is that I am taking you with me, and I'm anticipating us both to be approaching things in an emotionally open way. And then we will experience those realities and become better through it, become more aware, become more sensitive to other people’s experiences. I have a hard time using facts as kind of a bludgeon. We're surrounded by facts; what we're not surrounded by is meaning. That's what photography does best.

Is the emotional side, the empathetic side, the experiential side.

Absolutely. To me, the important thing is to make sure that I'm constantly feeling that my intention is pure and that I'm staying true to that. Then all these other things can come through. And what I mean by these other things is sometimes very specific things, in terms of documentary, but also very abstract things and things that are hard to pin down, feelings and emotions. But if all of those elements are encompassed in a true way, it comes across. It comes through.

Do you get a lot of response or do you get more response outside the US to this work or from Europe or elsewhere, or you do get more response in the US and other countries see this as a more exotic, or how does that work?

I talk to people from elsewhere, and they say this is the first thing they see when they come to America. They’re shocked by the visual, street-level reality of America. And I think that just points out... again, this myopia that we were talking about before, Fred, this blind spot that Americans have. It becomes so easy to unsee ourselves.

WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 10, 2016 DAYTON, OHIO

I take city bus #24 from Meijer supermarket to Northwest Hub, and then city bus #8 from Northwest Hub to downtown Dayton, $1.50.

Down Salem Avenue, the road is a washboard of potholes and cracks and the inside of the bus clatters over each one. The loose seats squeal and rattle, making music as we go. I view a sign out the window: “Presence on these premises prohibited.”

The bus’ loudspeaker plays advertisements: “Stop using drugs and find a new way to live today,” it says. “Apply for Medicaid today,” it advises. And a Budweiser ad, “5:00 is almost here."

Lorain, Ohio. 2016. Closed Republic Steel mill as seen from the Black River.

NOTEBOOK: SATURDAY, JULY 9, 2016 LORAIN, OHIO

“LIBERTY - TRUTH - JUSTICE - EQUALITY” reads the inscription on an abandoned building on Broadway and W. 6th Street in downtown Lorain. At an appliance store across the way, a woman tells me, “Everything is gone here.” Nearby, a billboard advertising for a law office reads, “Loss of income does not mean loss of home.”

Geography

Flint, Michigan (2015)

THE FLINT WATER CRISIS: A TIMELINE

1855 Flint village incorporated.

1903 Buick Motor Company moves from Detroit to Flint.

1908 William C. Durant founds the General Motors Company in Flint.

1960s-70s General Motors employs over 80,000 people in Flint.

1960 Flint reaches its peak population of 196,940.

1980s GM begins to close its auto plants and lay off workers.

1986 Pure lead pipes, fittings, and solder are banned from water systems in the U.S.

1991 The U.S. Lead and Copper Rule establishes national regulations for testing lead and treating water supplies for the public.

1998 Buick Motor Division administration moved out of Flint and to Detroit.

1999 Buick City plant closed.

2011 The City of Flint has a $25-million dollar deficit and cedes control to the state. An emergency manager is appointed by Governor Rick Snyder to cut costs for the city.

2013 - 2014 For 50 years, Flint piped in corrosion-inhibitor-treated water from Detroit, but in an attempt to save money, the city changes its drinking water supply from Detroit’s system to the corrosive water of the Flint River. This is meant to supply water to residents until a new pipeline is built from Lake Huron. No corrosion inhibitors are added to the river water. The “new” water starts flowing through taps on April 25, 2014.

2014, August Fecal coliform bacteria is found in city water. Flint issues multiple “boil water” advisories to residents. The city adds more chlorine to the water, but this causes high levels of total trihalomethane, cancer-causing chemicals. Underlying problems with the water are not addressed.

2014, June - 2015, October Flint suffers an outbreak of Legionnaires’ Disease, sickening 87 people and killing 12: the third largest outbreak ever recorded in the U.S.

2014-2016 For a year and a half, corrosive Flint River water causes lead to leach out of aging pipes into Flint homes. Residents experience discolored water that smells and tastes bad, as well as cases of rashes, itchy skin, and hair loss. To almost 9,000 Flint children, lead-laced water is supplied for 18 months and in many, the bad water in the pipes results in lead levels two to three times the acceptable limit. Residents complain, but there is little governmental response.

2014, October A General Motors plant in Flint says it will no longer use Flint water because the elevated level of chloride causes corrosion on engine parts for cars.

2015, January Detroit offers to reconnect Flint to its water system for free, but city official refuse, citing increased costs.

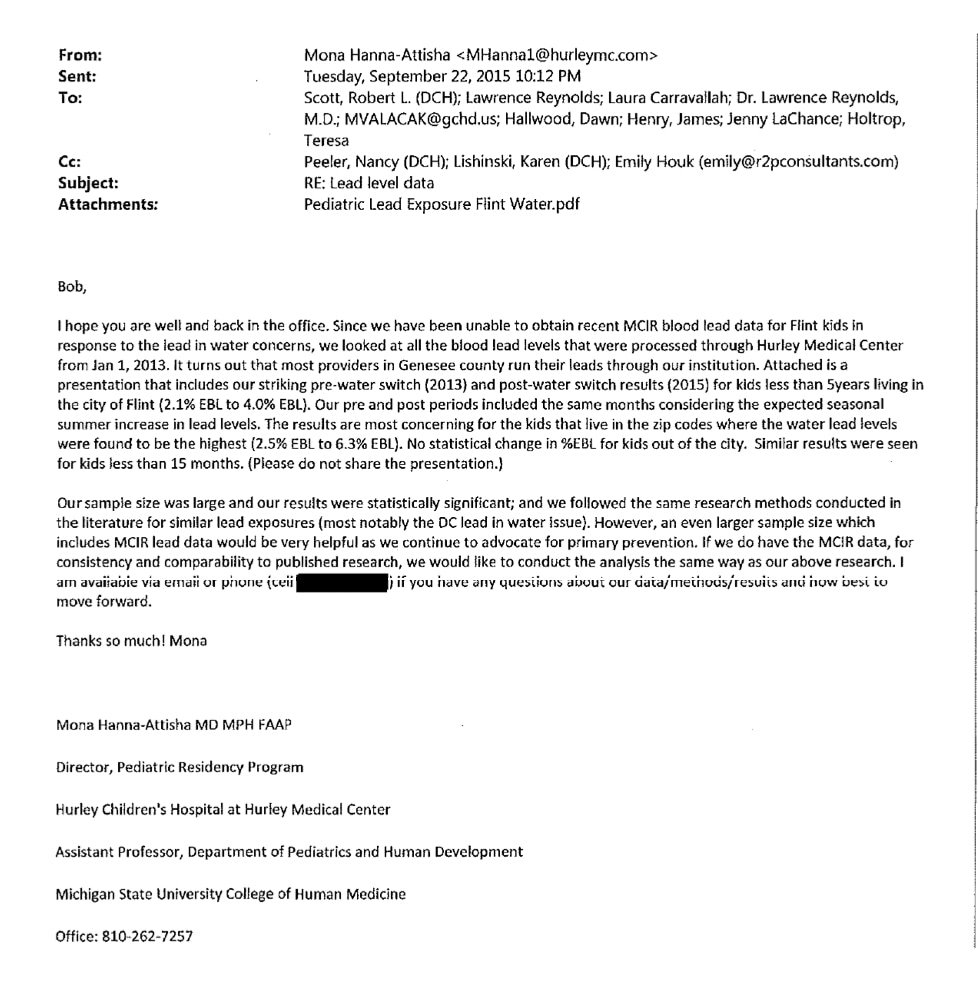

2015, Fall A study by researchers at Virginia Technical University finds that water samples, collected from 252 households, show almost 17% register above the federal “action level” of 15 parts per billion, or ppb. More than 40% measure above 5 parts per billion for lead, and several samples measure above 100 parts per billion. Flint’s water is found to be 19 times more corrosive than water from Detroit.

A separate study led by a local pediatrician finds that lead levels in Flint’s children has almost doubled. The city issues its first lead advisory since leaving Detroit’s water system.

2015, December President Barack Obama declares a federal emergency in Flint.

2016, April The first of 15 government officials has criminal charges filed against them for causing or contributing to the crisis.

2016, November A federal judge orders that every Flint home without a filter receive bottled water.

2016, December A $100-million bill to address the lead contamination is approved by the U.S. Senate.

2017, March A court settlement requires the city of Flint, using funds from the state of Michigan, to replace thousands of aging pipes that contain lead. In addition, more funding is to provide testing, continued bottled water delivery, education, and health programs for residents.

2020 Flint's population continues to dwindle, reaching a new low of 81,252.

2021 GM employs 5,000 people in Flint, down from 80,000.

2020, August Water crisis victims are awarded $600 million in a combined settlement.

2021, January Governor Rick Snyder and other officials are charged with felonies and misdemeanors for the crisis.

Voices, Flint, Michigan (2015)

“Can’t bathe in it. Can’t cook with it. Now they say you can’t even flush the toilet in it. They say the water in the bottles is no good either. I’ve got two little kids. I don’t bathe them in the water. Most of the time, I just wipe them down with the baby wipes. The whole government is responsible. I want to leave Flint. I’m scared to have my baby here now, and I’m due in two months.”

“People were saying how it tastes bad, it smells bad, it’s a different color. But the city was saying, ‘The water is fine; there is nothing wrong with it.’ Then the next day they were saying, ‘It can kill you.’”

“I’m just so afraid, I’m terrified. There’s that fear. About a month ago, I’m going to tell you the truth, it got to me. I thought, ‘I need to see a professional.’ You know what my biggest fear is? That people are going to forget about us.”

“The disease specialist came in and told me I had listeria. I cooked in the water, I drank the water, and I was hurt by it. The water caused my baby to almost die. We need to fix it. He’s still getting exposed to it because we wash his clothes in it. I wish I could move, but money right now is not allowing it.”

“The doctor said it’s from bathing in the water. It has a sunburn-y, tingly feeling to it. You would not purposely put yourself in this position.”

“I’m not in health enough to carry water. Cooking, washing, trying to tote water and all that. Who got punished for it? To me, it's never going to end.”

"This is a place of poverty. Who’s going to notice? Who cares? It’s a big battle, trying to find hope in the midst of a city where there is no trust.”

“If this city was not 60 percent black, 40 percent poor, this problem would have been fixed already. We still don’t know the end of all this. There are the working poor, and then there are the poor. We are the poor.”

"If it was higher economic areas, they would have checked it out sooner. I don't think they paid attention. The government didn't listen. They don't care. They let it go. It's not just the water problem, look at the school buildings. Our whole consciousness is skewed. Now people have a voice. Everyone got together. But now everyone is pointing a finger at everyone else. I’m concerned about what is going to happen to the children. The poor are impacted more.”

“You’d never think this could happen here. This is a city that used to be gigantic, and then we just went down and down, and finally, we’ve hit rock bottom.”

“Water is not supposed to look like urine. I noticed that my hair was falling out, and my neck started breaking out, and my feet started cracking real bad. One of the things that hit me the worst is when I see the kids who've tested positive for lead. I have to look at my son with two big old spots on his head.”

“We’ve kinda created our own Hiroshima. Generations from now, we’ll still be feeling the effects.”

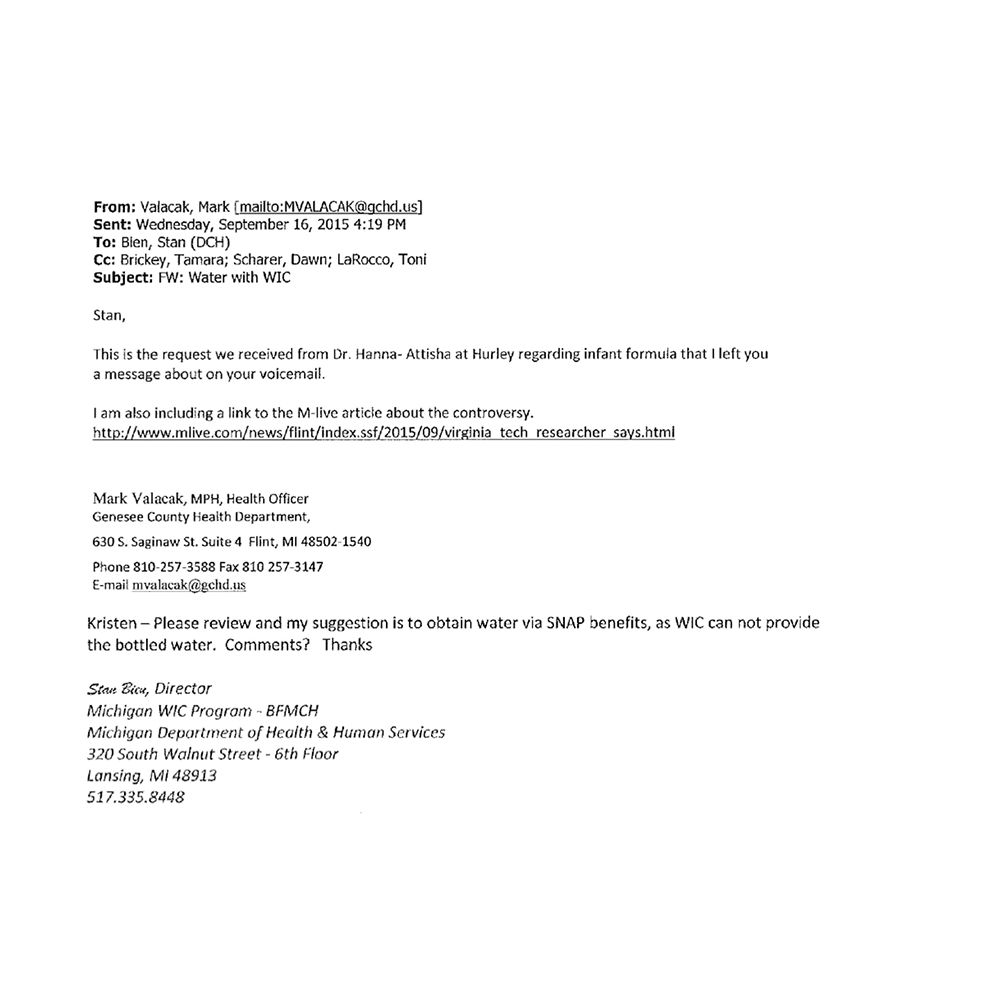

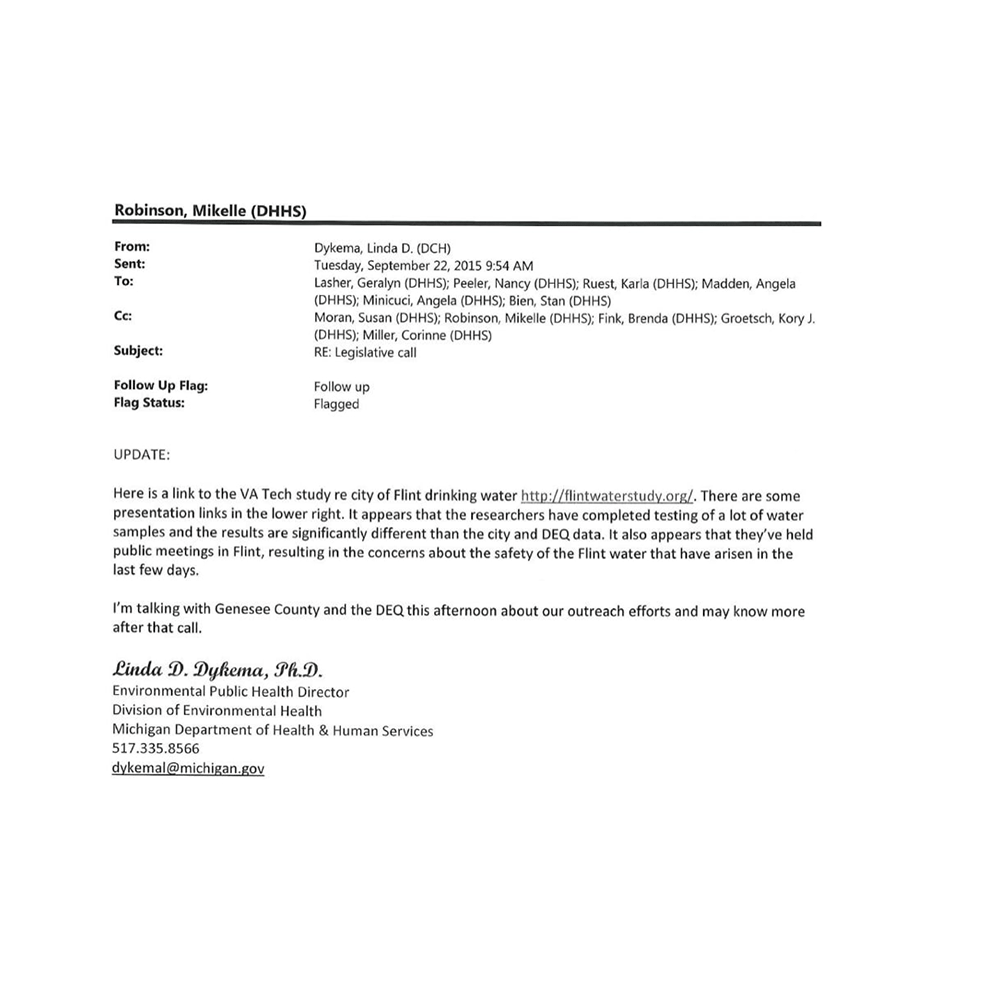

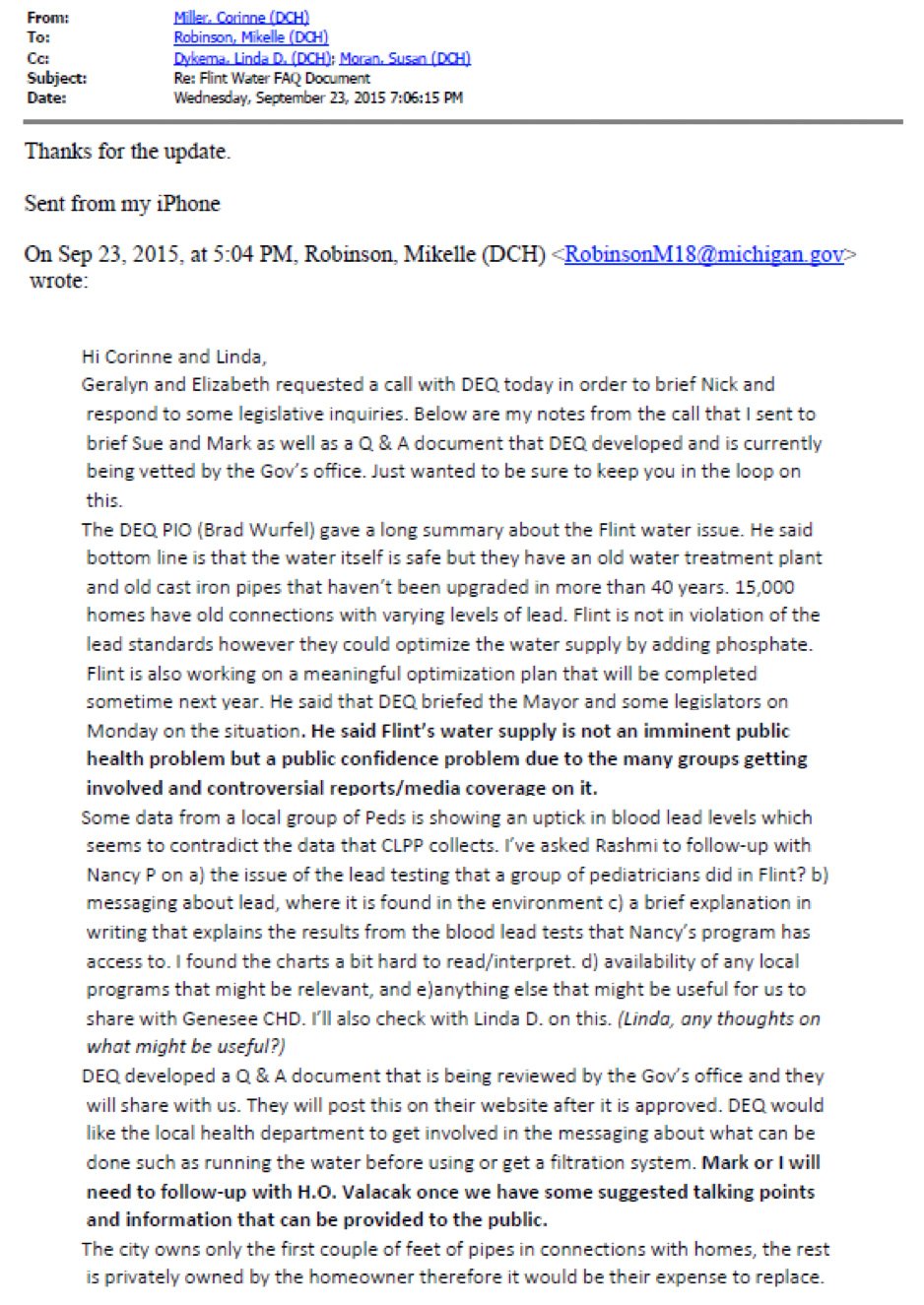

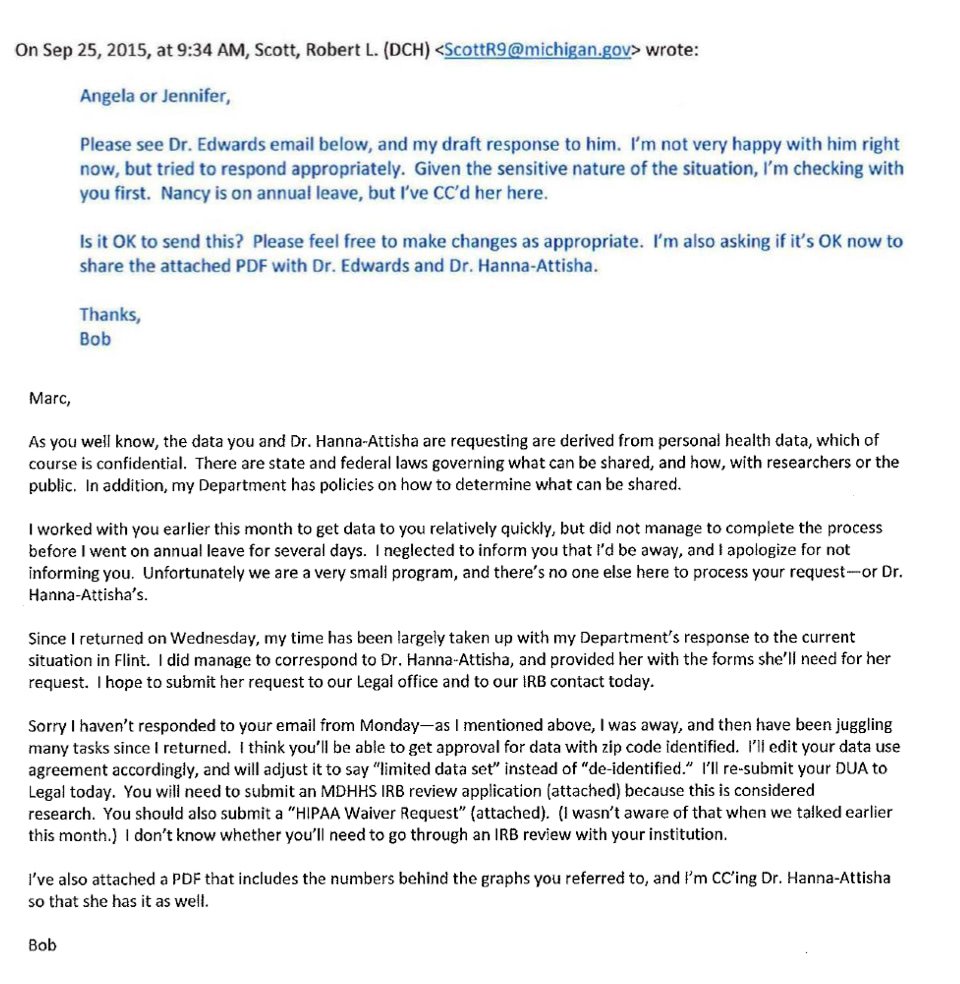

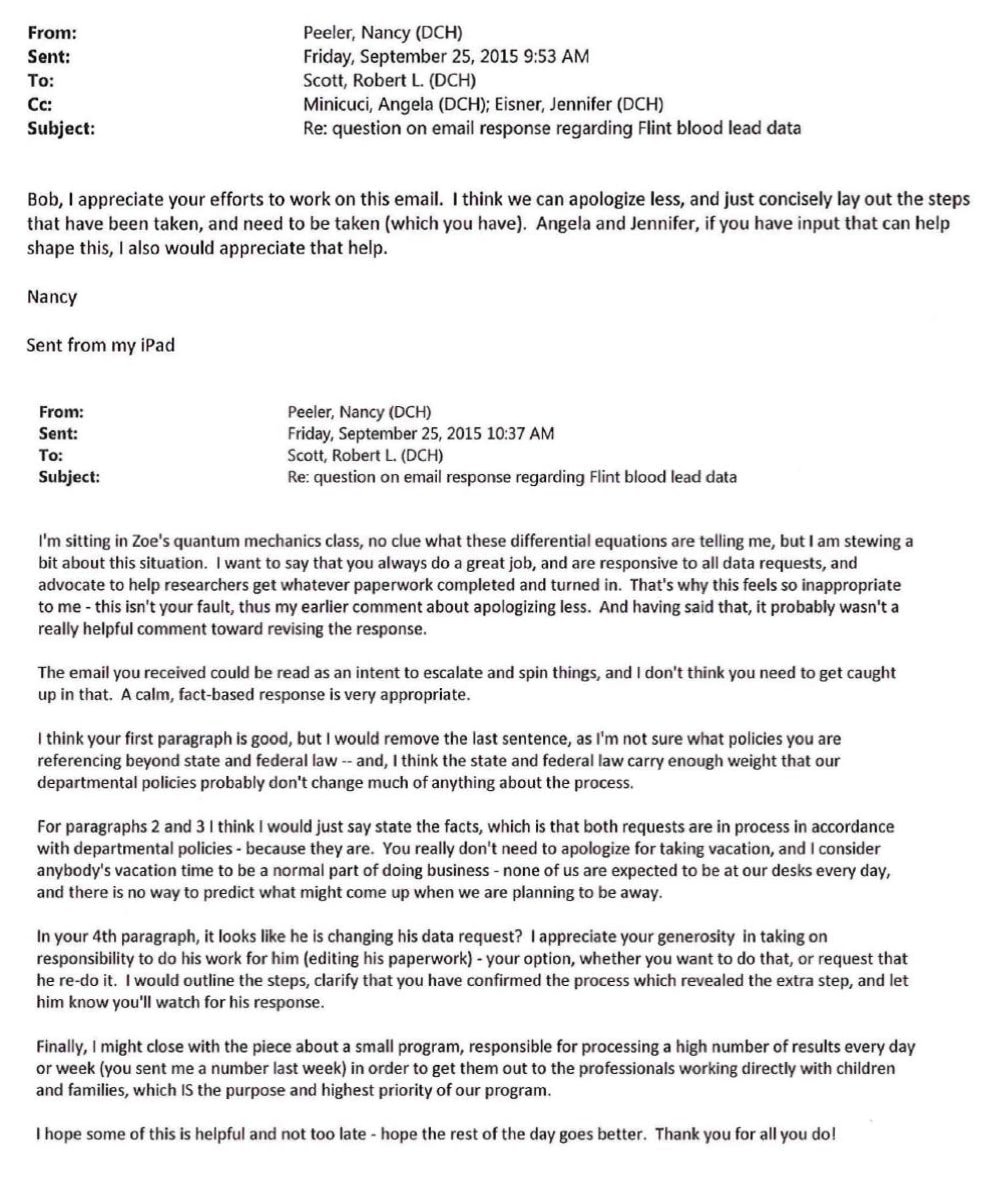

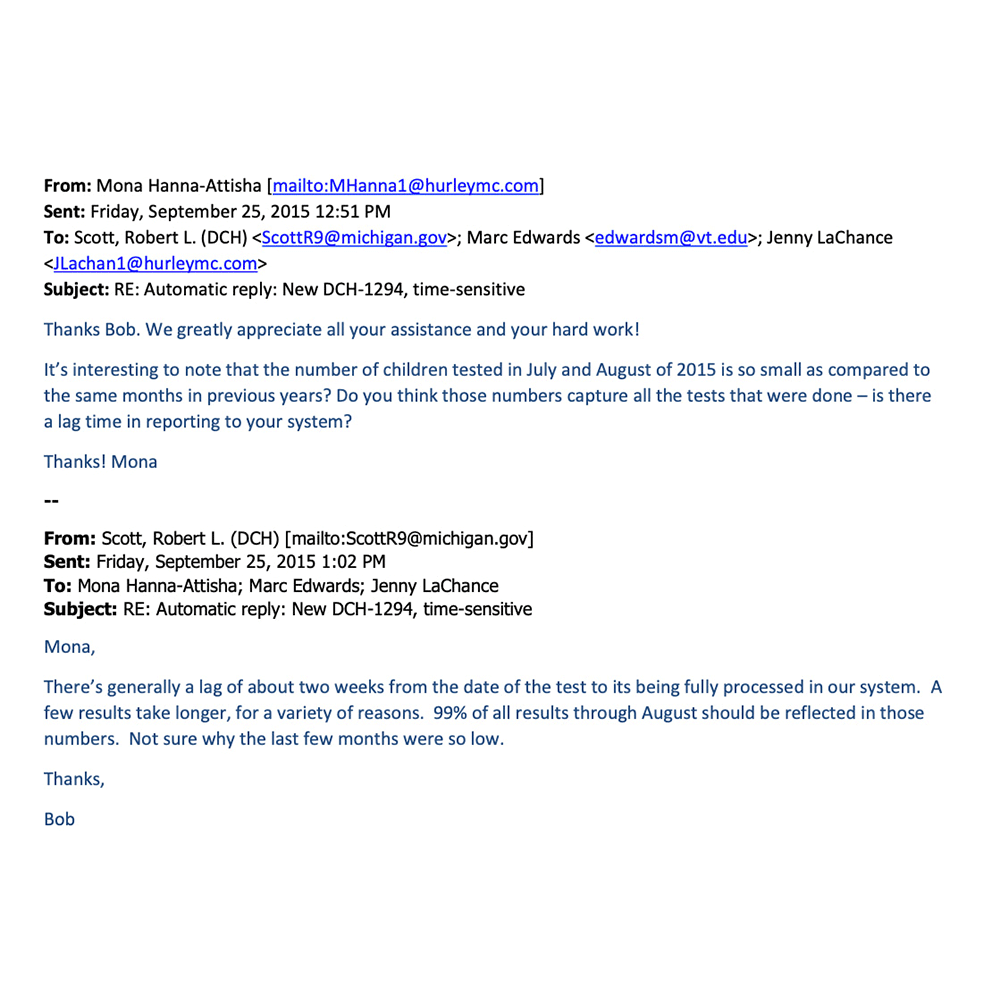

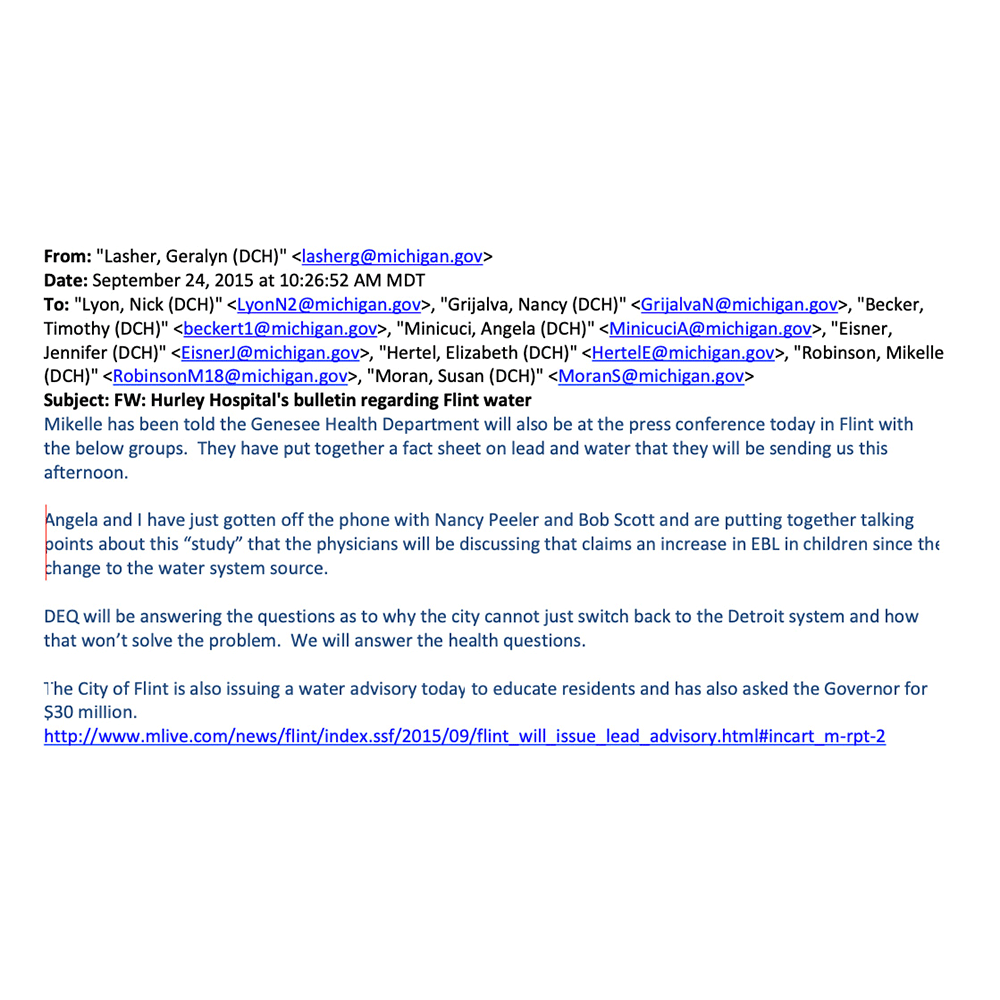

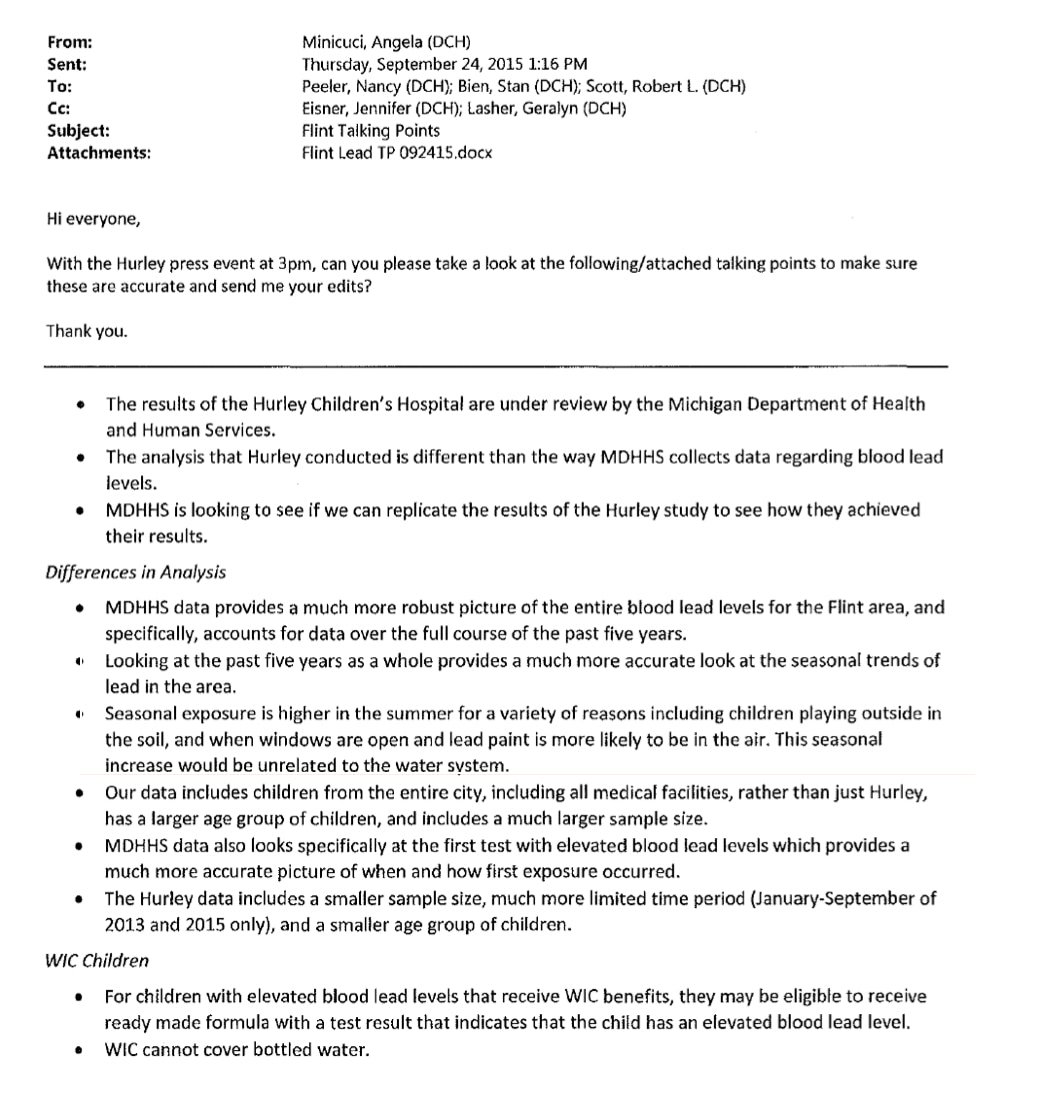

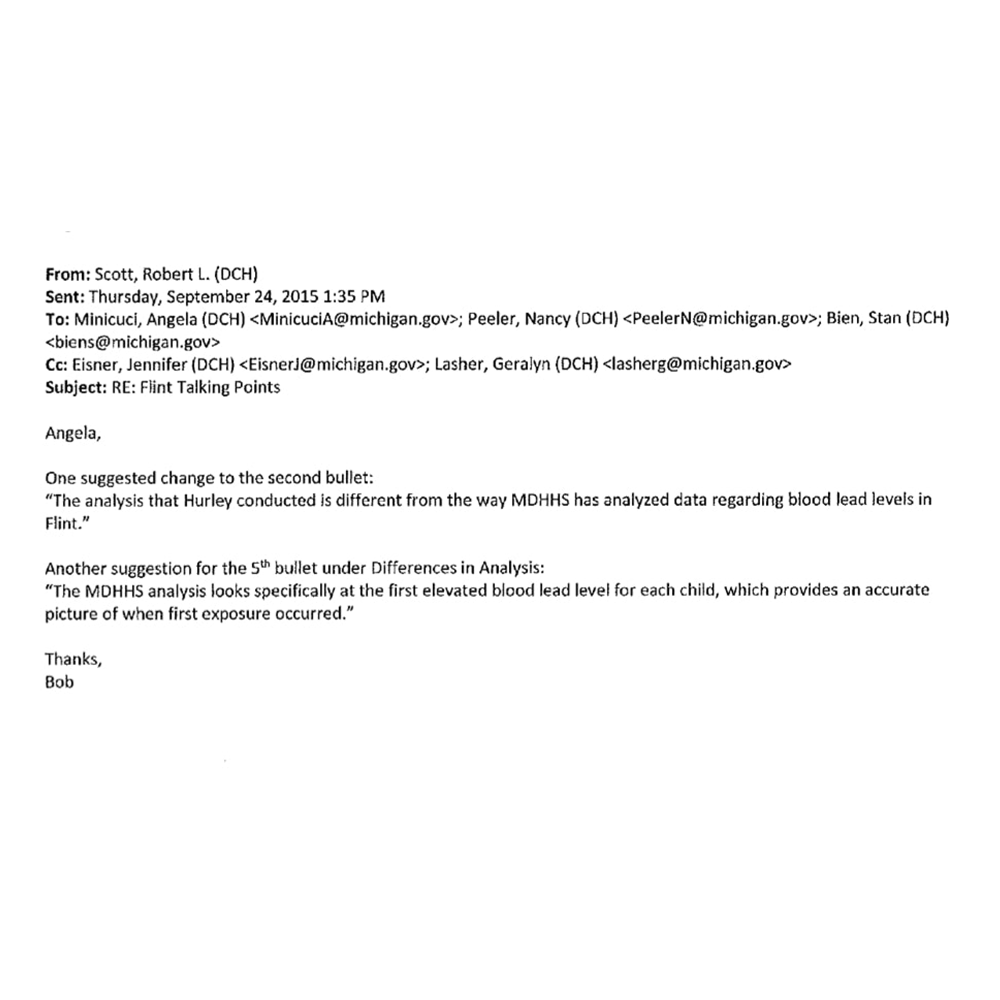

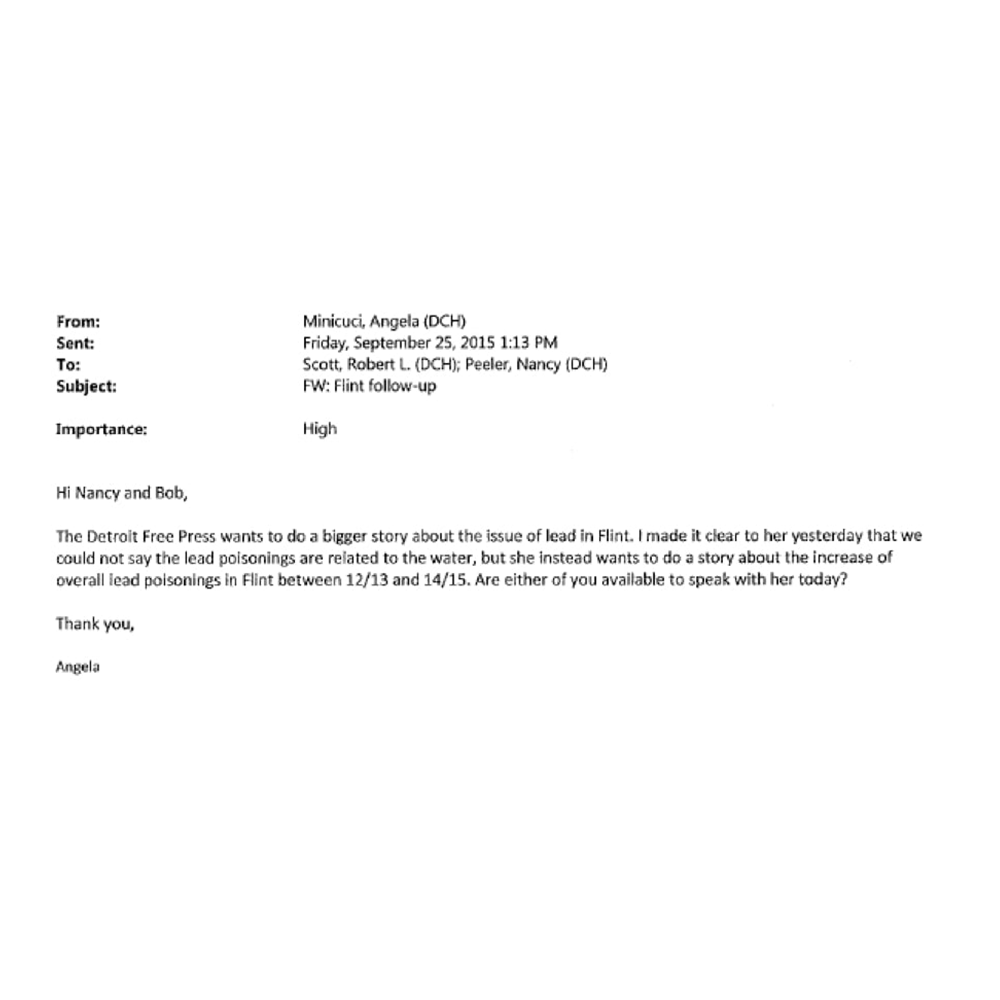

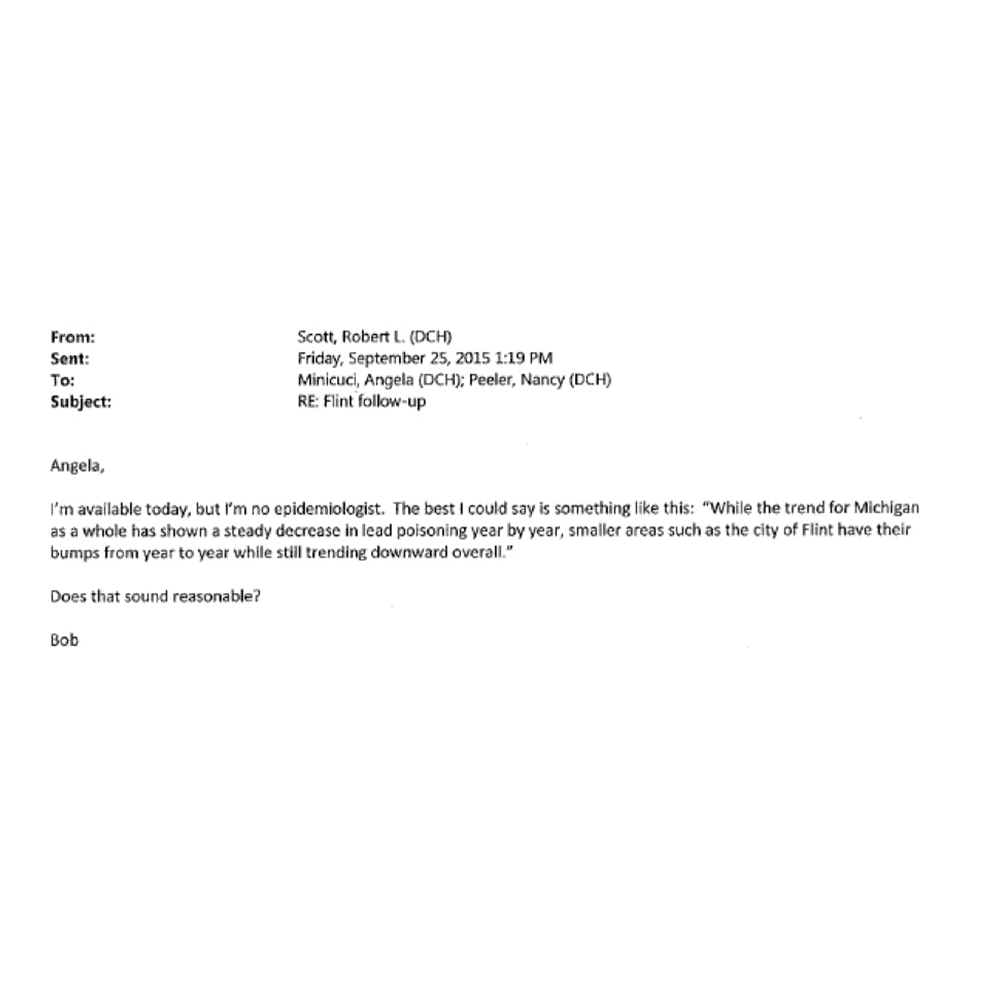

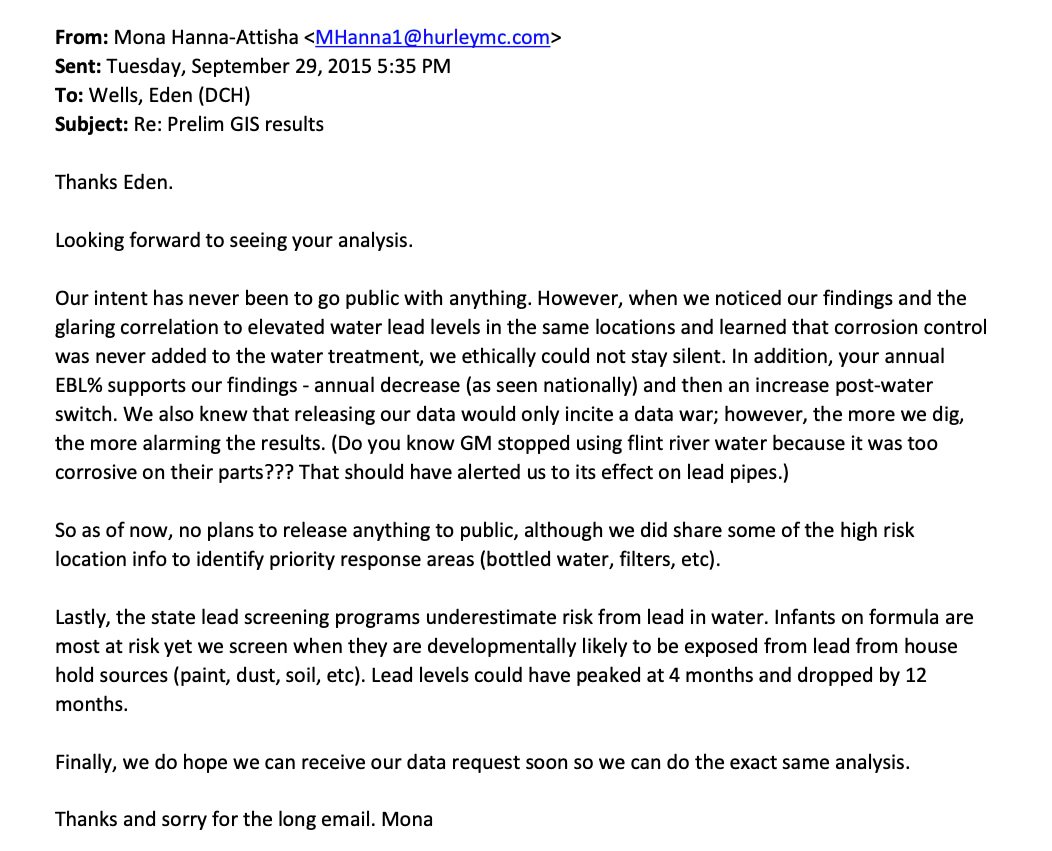

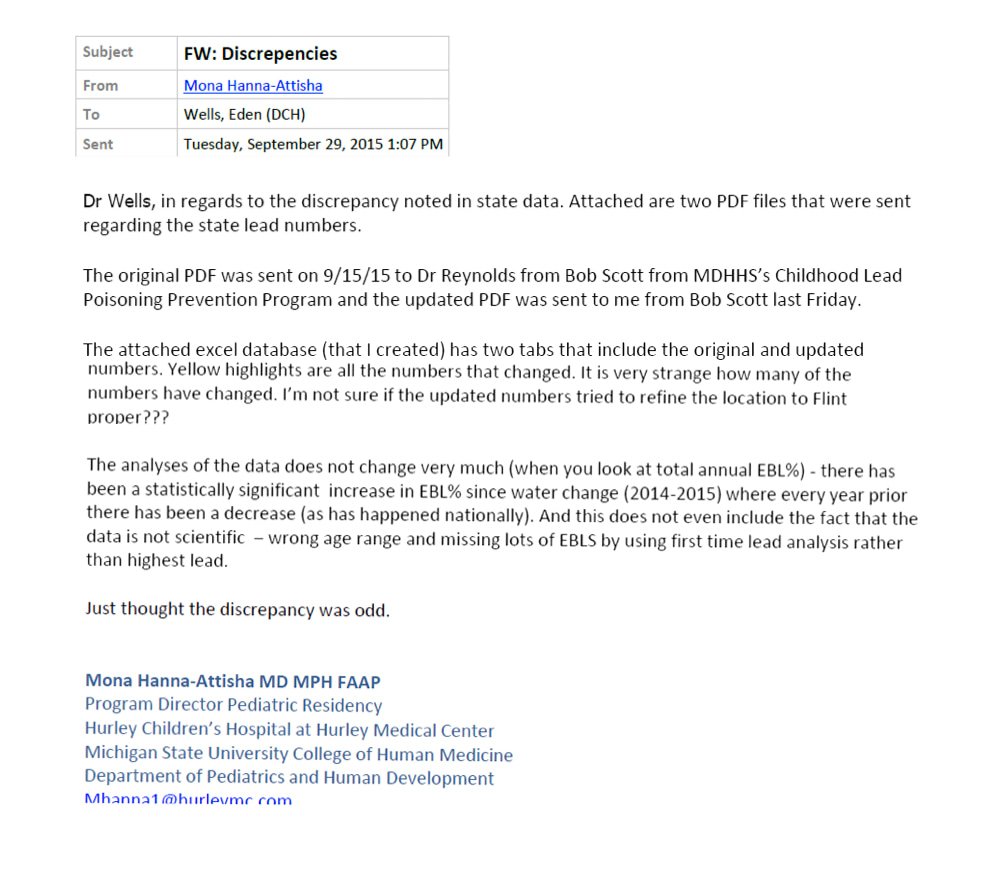

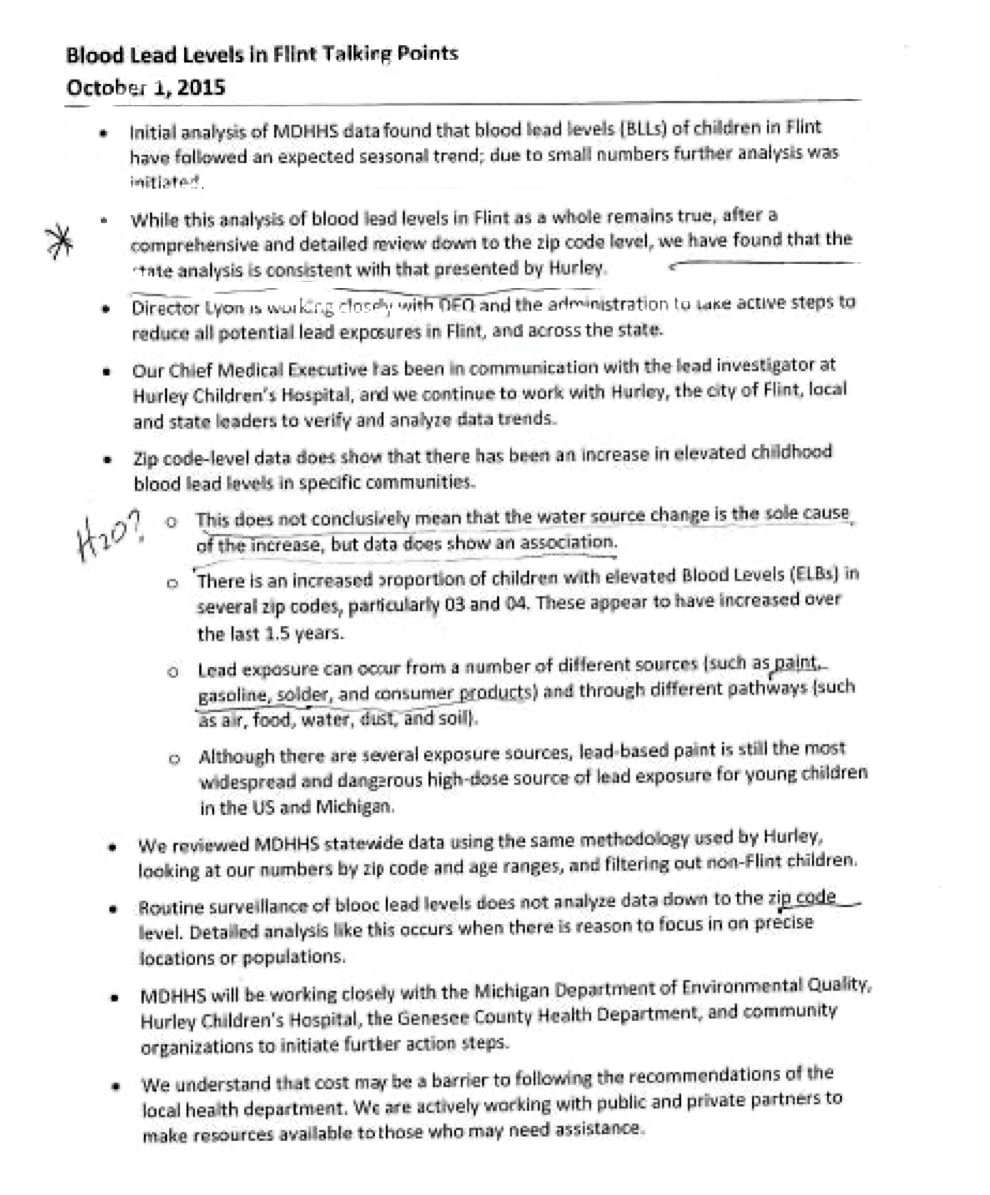

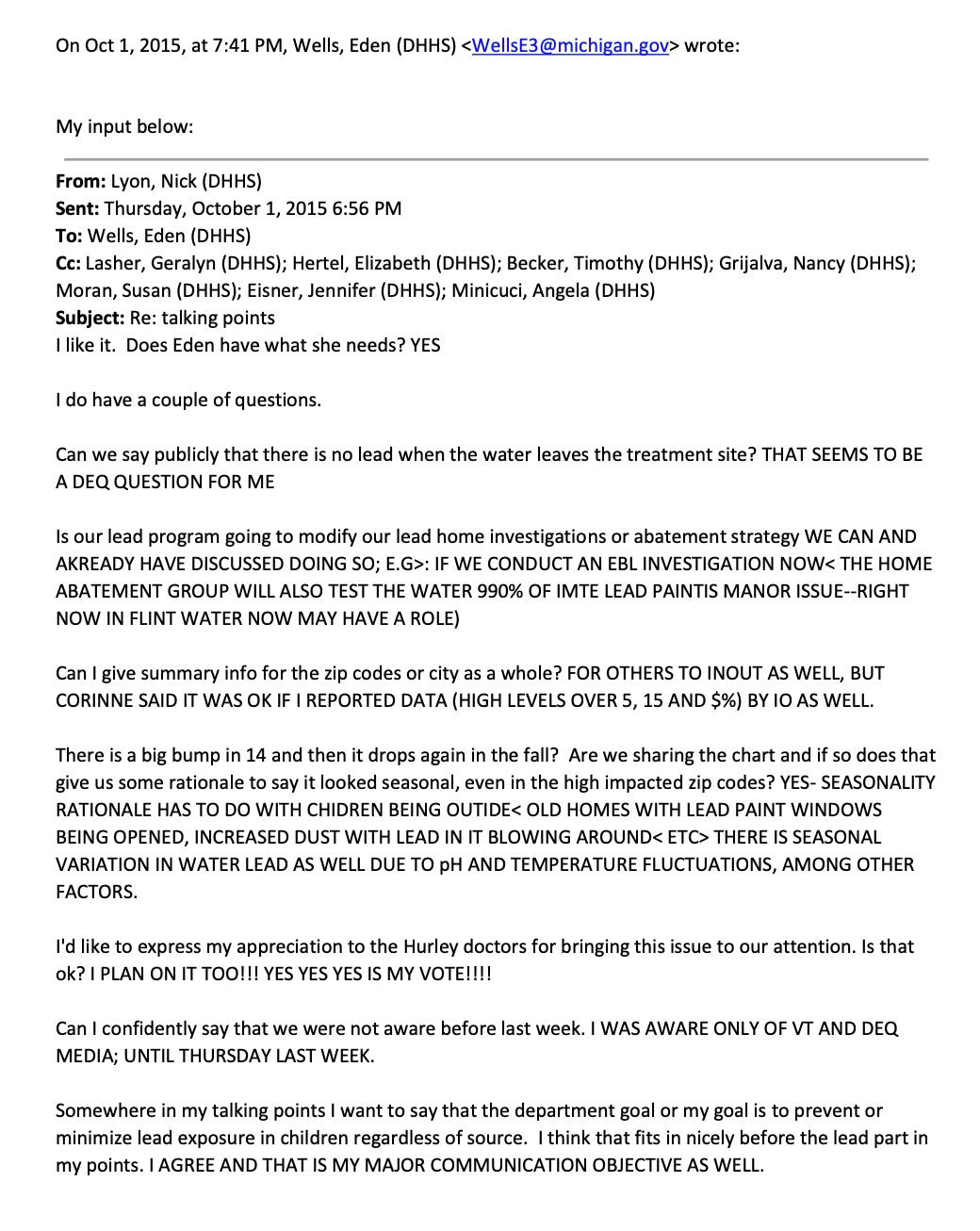

Emails: Flint, Michigan (2015)

Nine public officials were eventually charged for their roles in the Flint, Michigan, water crisis that led to thousands of residents being exposed to lead via their city drinking water, after the safe source out of Detroit, used for years, was traded for cheaper pumping out of the Flint River with no provisions made for the corrosive, often-tainted water. As a result, a deadly Legionnaire’s outbreak cost lives, and as lead leached into homes, children were irreparably affected by lead poisoning.

Officials charged included former Governor Rick Snyder; head of the state Health Department Nick Lyon; state chief medical executive Dr. Eden Wells; health official Nancy Peeler; Snyder’s top aide Rich Baird; Snyder’s chief of staff Jarrod Agen; public works director Howard Croft; and emergency managers Gerald Ambrose and Darnell Earley. Charges — 41 in all — ranged from involuntary manslaughter to misconduct in office, obstruction of justice, extortion, perjury, and suppression of EBLL (Elevated Blood Lead Levels) data in the children of Flint.

SATURDAY, AUGUST 8, 2015, FLINT, MICHIGAN

Someone stripped all the metal siding off dozens of trailers in a vacant mobile home park on the edge of town. They look like beached whales, humpbacked with their ribs exposed. Old mattresses, broken shoes, and half-stuffed black trashbags litter the ground. I come upon a stack of someone named Lora’s important papers. “I don’t have a current Doctor and requested the General Free Clinic for my records and none were sent. I also lost my food stamps in February of this year. I currently have no employment or income,” reads one.

Inside a trailer, a box of freeze-dried mashed potatoes lies tipped on its side on a countertop. In another, an empty bottle of Crown Royal sits with three coffee mugs and a phone book opened to “Dentists.” On the floor, mixed into some clothes, are family photos: prom night, first day of school, and two siblings, well-groomed and smiling, sitting at a dinette table.

I go to a soup kitchen, where I meet Patricia. “Money is not evil, people always say it’s ‘the root of all evil,’ that’s not true. Money is the root of our frustrations and when you don’t have it, it causes you to do evil,” she says.

I drive to north Flint, past Buick City, once the largest car plant in the world, now an empty concrete slab surrounded by a cyclone fence.

American Geography: Bookshelf

Agee, James, and Walker Evans. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. 1941. Introduction by John Hersey. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, 1988.

Adams, James, Truslow. The Epic of America. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, & Co., 1931.

Arax, Mark and Rick Wartzman. The King of California: J.G. Boswell and the Making of a Secret American Empire. New York: Public Affairs, 2003.

Balderrama, Francisco E. and Raymond Rodriguez. Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s. University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011.

Caudill, Harry M. Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area. Foreword by Stewart L. Udall. Boston: Little, Brown, & Co. 1962.

de Crevecoeur, J. Hector St. John. Letters from an American Farmer. 1782. Edited and introduction by Albert E. Stone. Penguin Classics, 1987.

Finnegan, Cara A. Picturing Poverty : Print Culture and FSA Photographs. Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2003.

Goldschmidt, Walter. As You Sow. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1947.

Haslam, Gerald W. Workin’ Man Blues: Country Music in California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999.

Hendrickson, Paul. Looking for the Light: The Hidden Life and Art of Marion Post Wolcott. Alfred A. Knopf, 1992.

Lange, Dorothea, and Paul Taylor. An American Exodus: A Record of Human Erosion. The University of Michigan, 1939.

Lange, Dorothea. Farm Tenancy: First Published Photographs. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1937.

Lange, Dorothea. Farm Security Administration Photographs:1935-1939. Library of Congress/Text-Fiche Press, 1980.

Levine, Philip. 1933. Poems. New York: Atheneum, 1974.

Levine, Philip. A Walk with Tom Jefferson. Poems. New York: Knopf /Doubleday, 1988.

Levine, Philip. What Work Is. Poems. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991.

Levis, Larry. Winter Stars. Poems. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1985.

McDaniel, Wilma Elizabeth. The Red Coffee Can. Fresno: Valley Publishers, 1974.

McWilliams, Carey. Ambrose Bierce: A Biography. New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1929.

McWilliams, Carey. The Education of Carey McWilliams. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1979.

McWilliams, Carey. Factories in the Field: The Story of Migratory Farm Labor in California. Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co, 1935, 1939.

Nixon, Herman Clarence. Forty Acres and Steel Mules. The University of North Carolina Press, 1938.

Nixon, H.C. Lower Piedmont Country. New York, J. J. Little & Ives, 1946.

O’Neal, Hank. A Vision Shared, A Classic Portrait of America and Its People 1935-1943. Forward by Bernarda Shahn, afterword by Paul S. Taylor. St. Martin’s Press, 1976.

Richardson, Peter. American Prophet: The Life and Work of Carey McWilliams. University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Rodriguez, Richard. Hunger of Memory: The Education of Richard Rodriguez. David R. Godine, 1982.

Rodriguez, Richard. Days of Obligation: An Argument With My Mexican Father. Penguin Books, 1993.

Saroyan, William. My Name is Aram. Stories. New York: H. Wolff, 1940.

Saroyan, William. The Man With the Heart in the Highlands. New York: Dell Publishing, 1968.

Saroyan, William. Fresno Stories. New York: New Directions Bibelot, 1994.

Soto, Gary. The Elements of San Joaquin. Poems. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1977.

Steinbeck, John. In Dubious Battle. Covici Friede, 1936; Penguin Publishing Group, 1979.

Steinbeck, John. Their Blood is Strong. San Francisco, CA: The Simon J. Lubin Society, 1938.

Steinbeck, John. The Grapes of Wrath. New York: The Viking Press, 1939.

Stryker, Roy, and Nancy Wood, eds. In This Proud Land : America 1935-1943 As Seen In The FSA Photographs. New York Graphic Society. Greenwich. 1973.

Wartzman, Rick. Obscene in the Extreme: The Burning and Banning of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. New York: Public Affairs, 2008.

Weber, Devra. Dark Sweat, White Gold: California Farm Workers, Cotton, and the New Deal. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994.

Wilson, Charles Morrow. Roots of America: A Travelogue of American Personalities. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Co., 1936.

Wolcott, Marion Post. FSA Photographs. Introduction by Sally Stein. Carmel, CA: Friends of Photography, 1983.

Walking Main

A selection of old postcards from the places portrayed

in American Geography show a bygone vision.

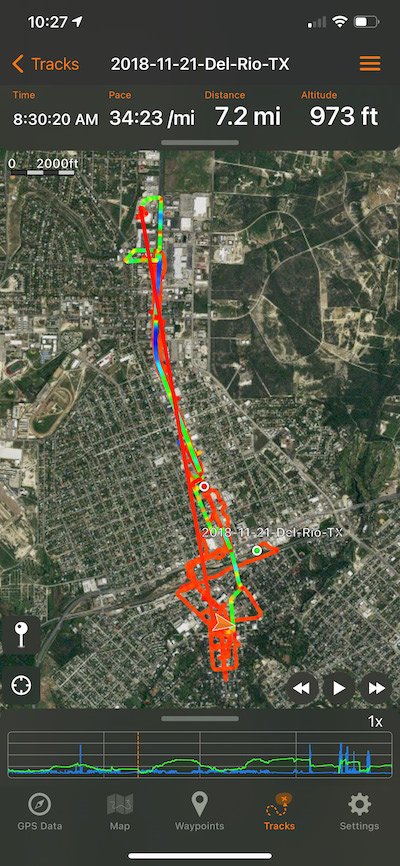

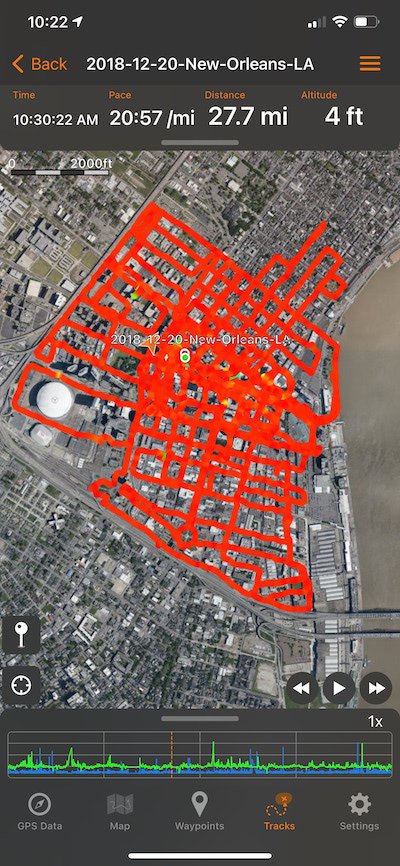

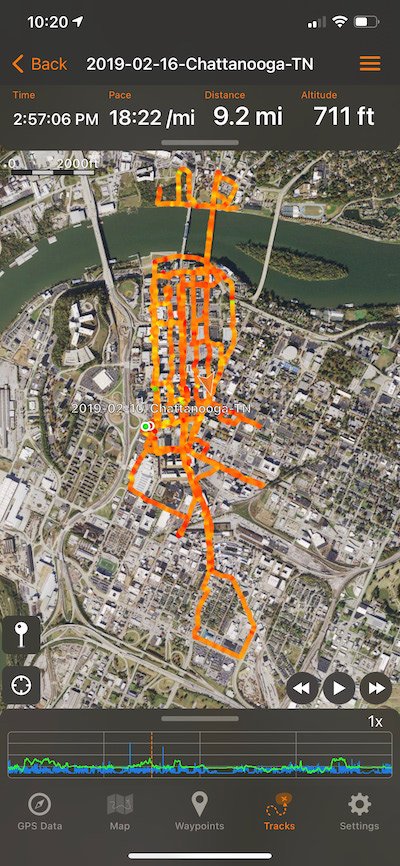

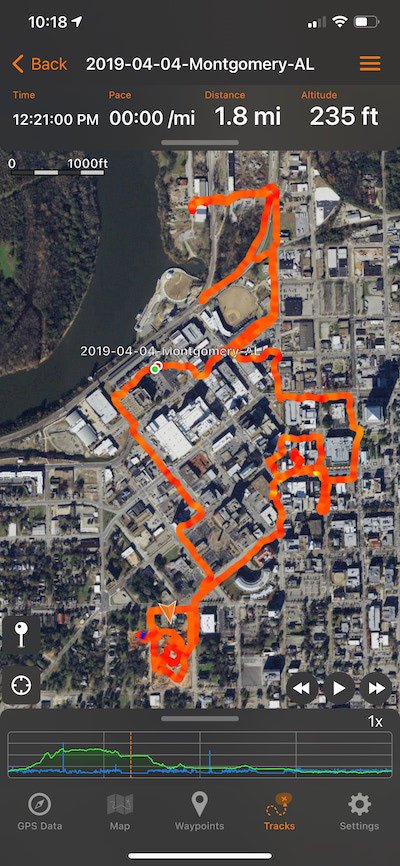

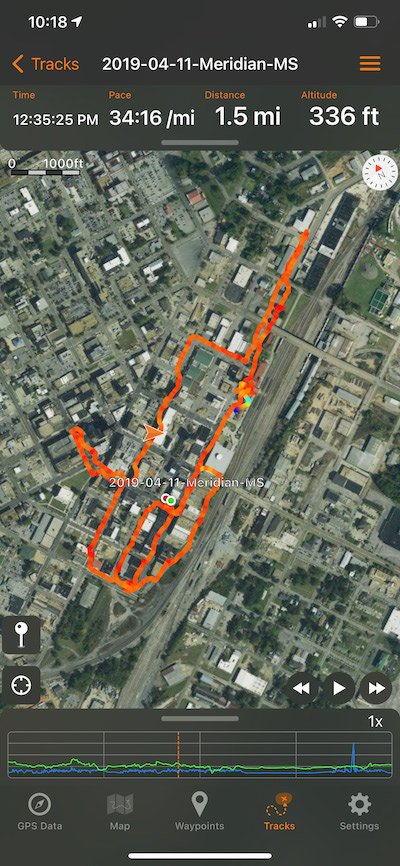

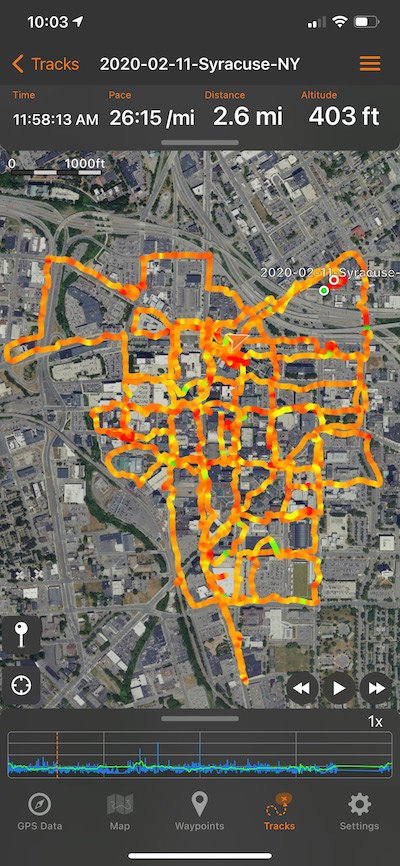

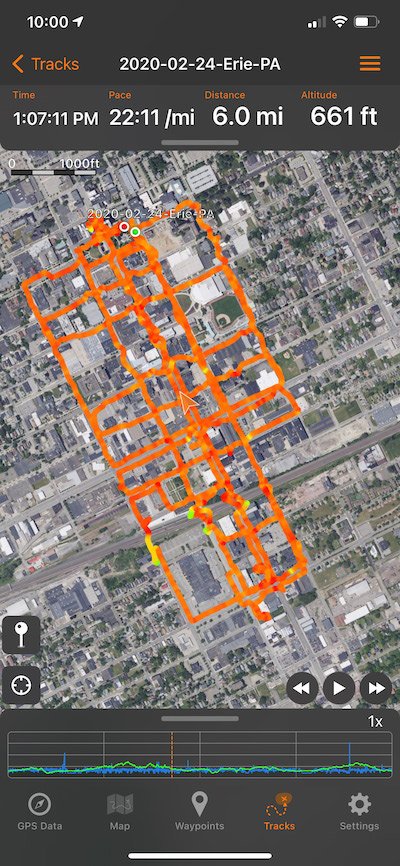

Matt Black GPS tracks

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 7, 2016 BELLINGHAM, WASHINGTON

“I used to work at a farm. The grower said if you worked for him you didn’t have to pay rent. But when I had the amputation, the grower said I didn’t work there. I was pruning raspberries. I think the boss wanted me dead because he never checked up on me. I wouldn’t wish it on anybody, because it is a sad story.

“I was seven months in the hospital. I lost a lot of blood. It was like the life of a dog in there. It took me a lot of time to recover. It was a bad situation. People don’t believe it. They think we come to this country to take jobs. But if you analyze it, it’s not that. Go out to the raspberry fields and see. You come here to try to have something, and then this happens. If I had money, I would buy new feet.”

---------------

TUESDAY, JULY 24th, 2018 MENDOTA, CALIFORNIA

Pedro and his son, Pedro Jr., live in what was once a highway motel, now converted into a house and rented for $900 a month. The outside is painted pink that’s faded to the hue of Pepto Bismol. The fence by the front door is decorated by Pedro Jr. smearing his hands in toothpaste and making white handprints all over the brown boards.

Two pigeons built a nest on a broken floodlight tucked in the peak of the roof. The empty nest balances on the slick enamel top of the light fixture, but when the birds lay eggs in it, the extra weight makes the nest slip and fall to the sidewalk. Pedro says it happens every year.

---------------

TUESDAY, MAY 14, 2019 CALEXICO, CALIFORNIA

Arnulfo lives in a shanty he built alongside the New River that runs across the border from Mexico. The most polluted river in America, it's said, the water smells of sewage and chemicals from hundreds of feet away. In front of his shanty, he has a fire pit, a beach umbrella, and a solar panel for charging his cell phone. On the side of his bike, he has strapped a machete. Every so often, he crosses to Mexico. “Over there, I’m a rich man; here, I’m just homeless.” Next door, his neighbor's shack has burned down, leaving a pile of charred planks, bits of tarp, and blackened paper.

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2020 EXETER, CALIFORNIA

Fall. Through farm fields north and west of home. The sky is overcast, the color of ashtray. Leaves still cling to trees, but just.

Bright red pomegranates hang like Christmas ornaments from yellowed trees. Big tubes of harvested cotton, rolled up in yellow plastic, are being hauled off the fields on flatbed trucks. On Kamm Avenue between Kingsburg and San Joaquin, a loaded-down alfalfa truck leaves a straw rain in its wake that dances off my windshield for a quarter mile.

I pass the harvested vineyards, the grape canopies between red and brown, the color of dried blood. Everything feels exhausted, both the land and me.