Part One:

The Valley

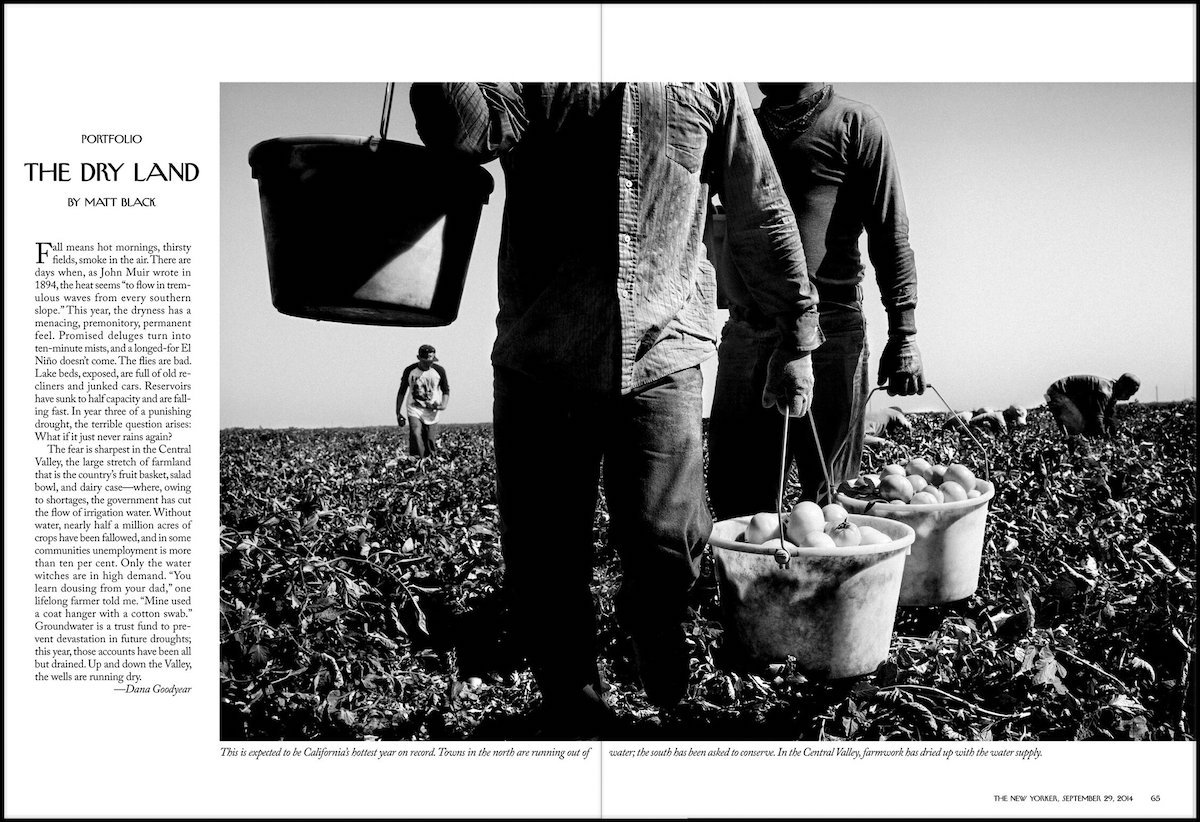

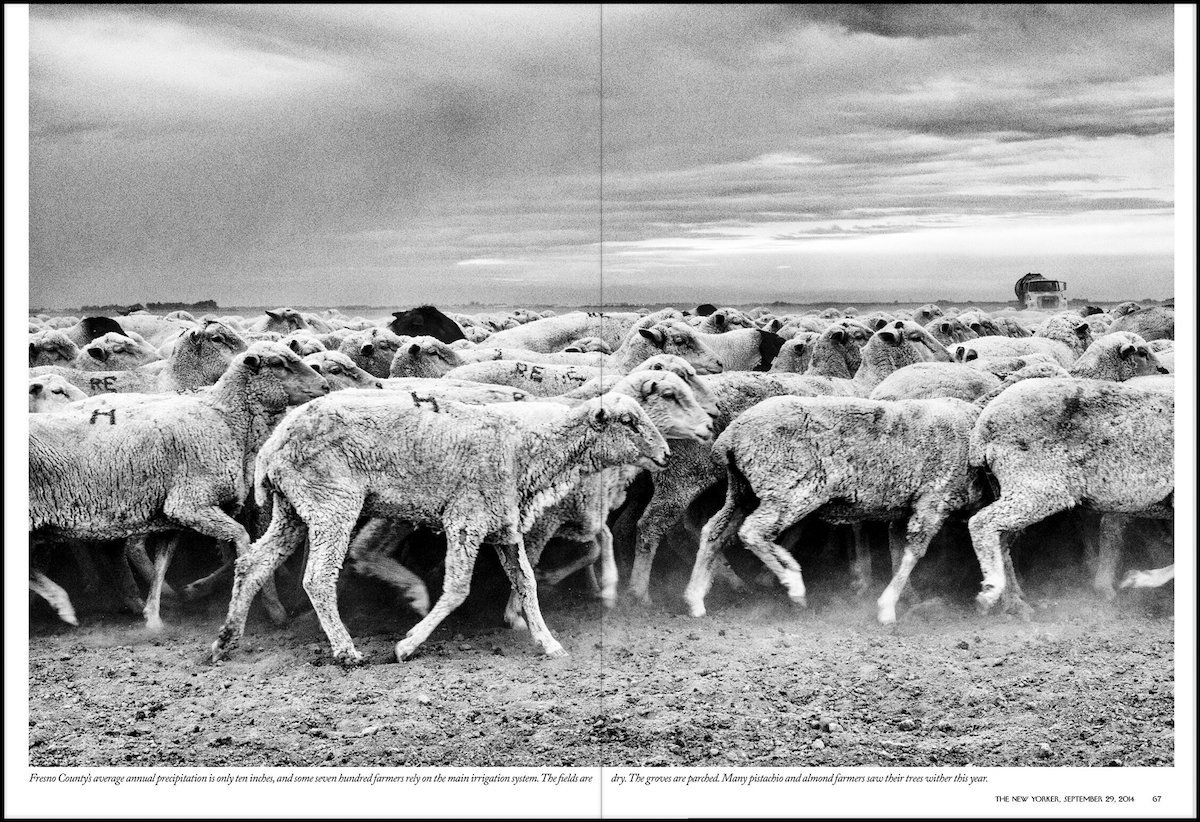

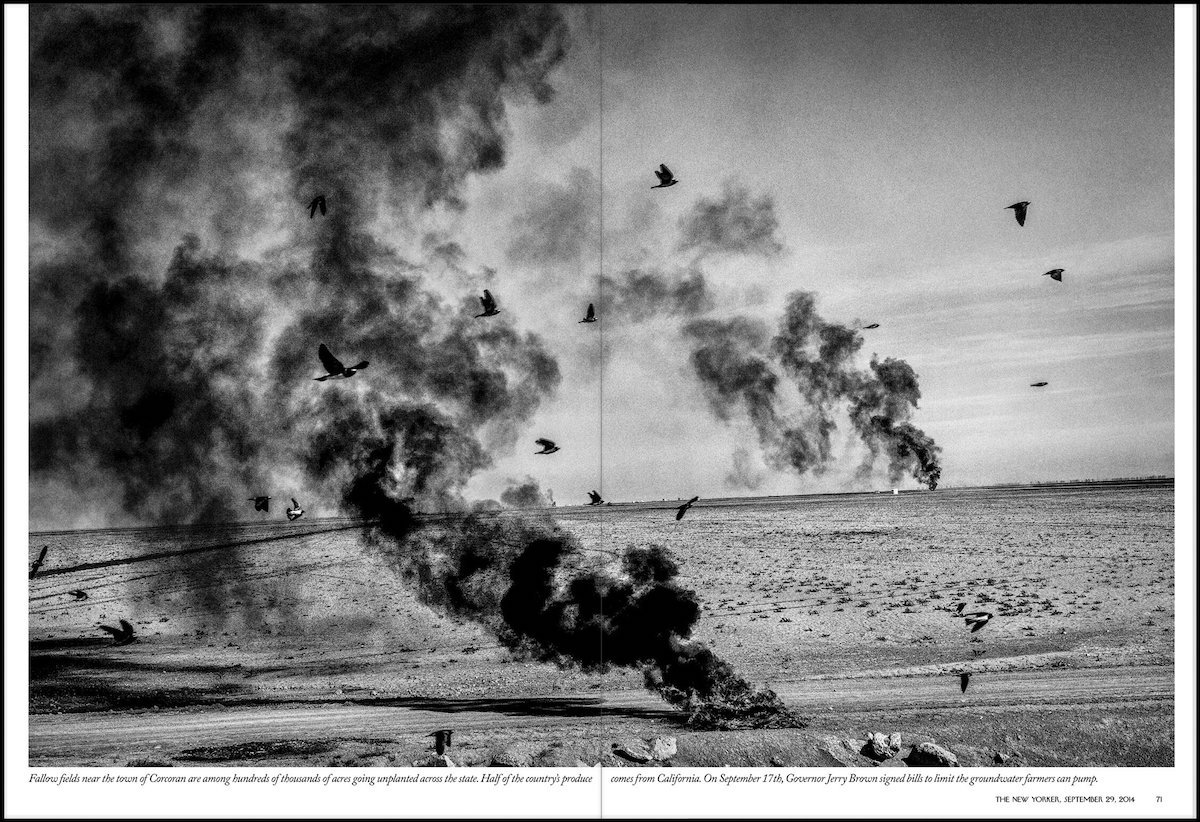

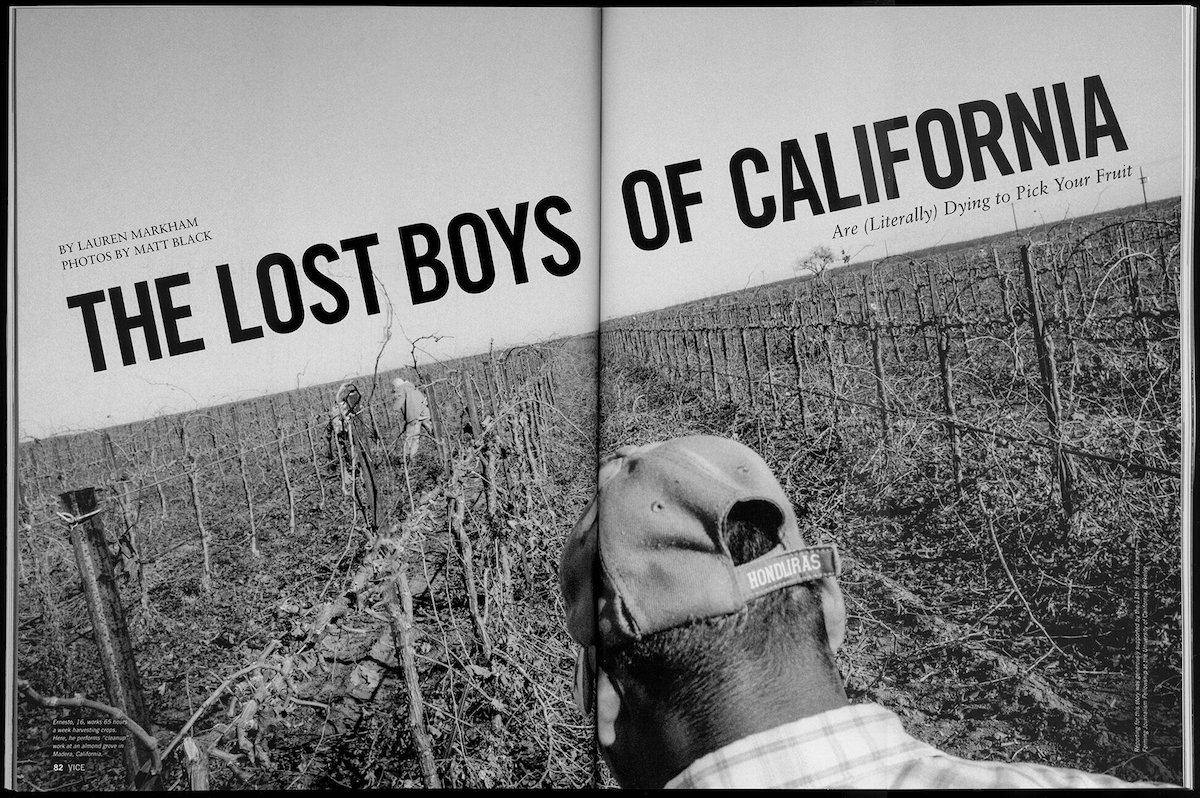

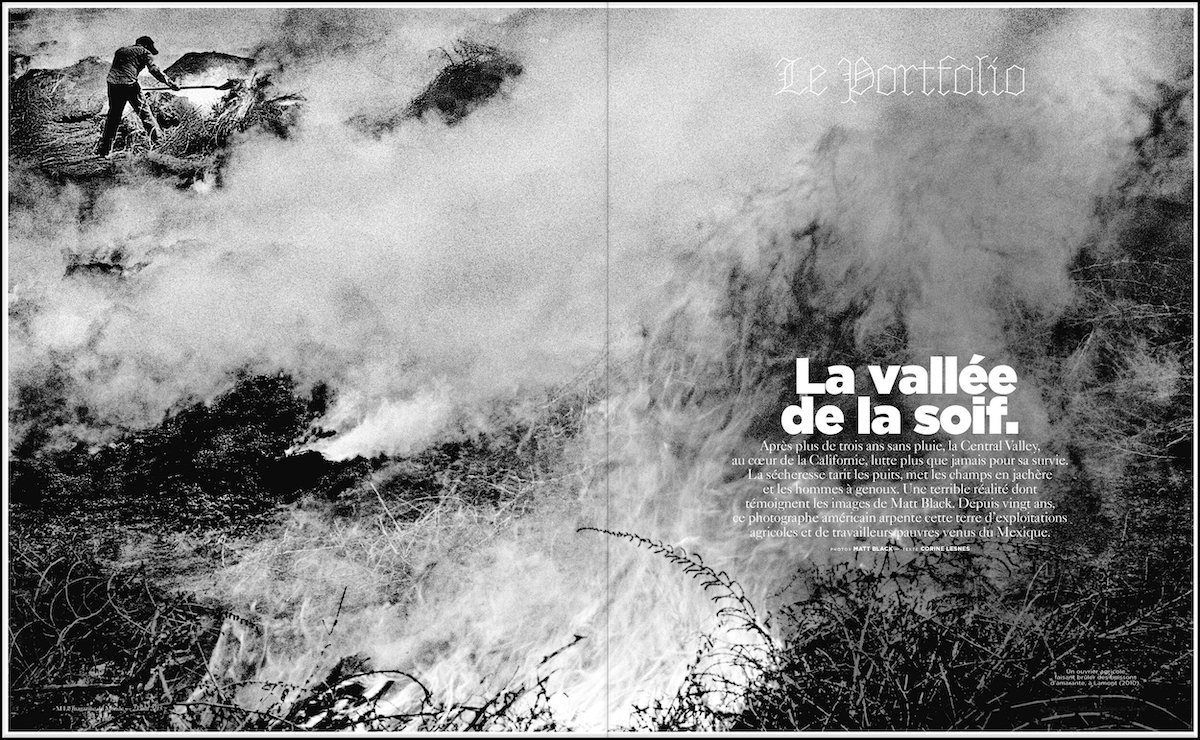

California’s Central Valley is divided into two halves, the upper, Sacramento, and the lower, San Joaquin. Together, they form one of the most productive farming regions in the world: more than 250 different crops, $40-billion worth of produce grown annually, and 40 percent of the country’s fruit, nuts, and “table foods” each year.

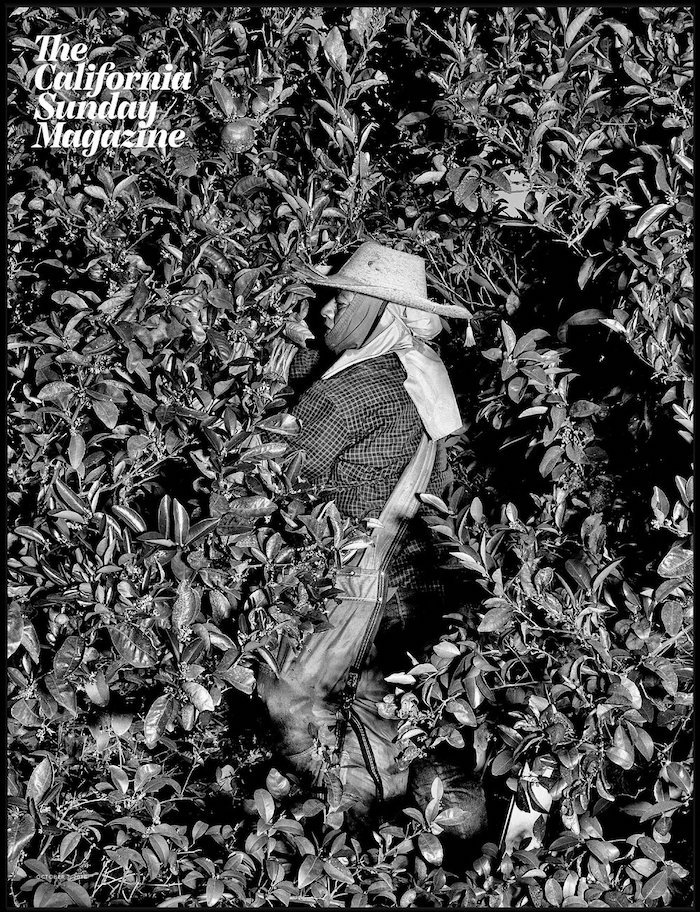

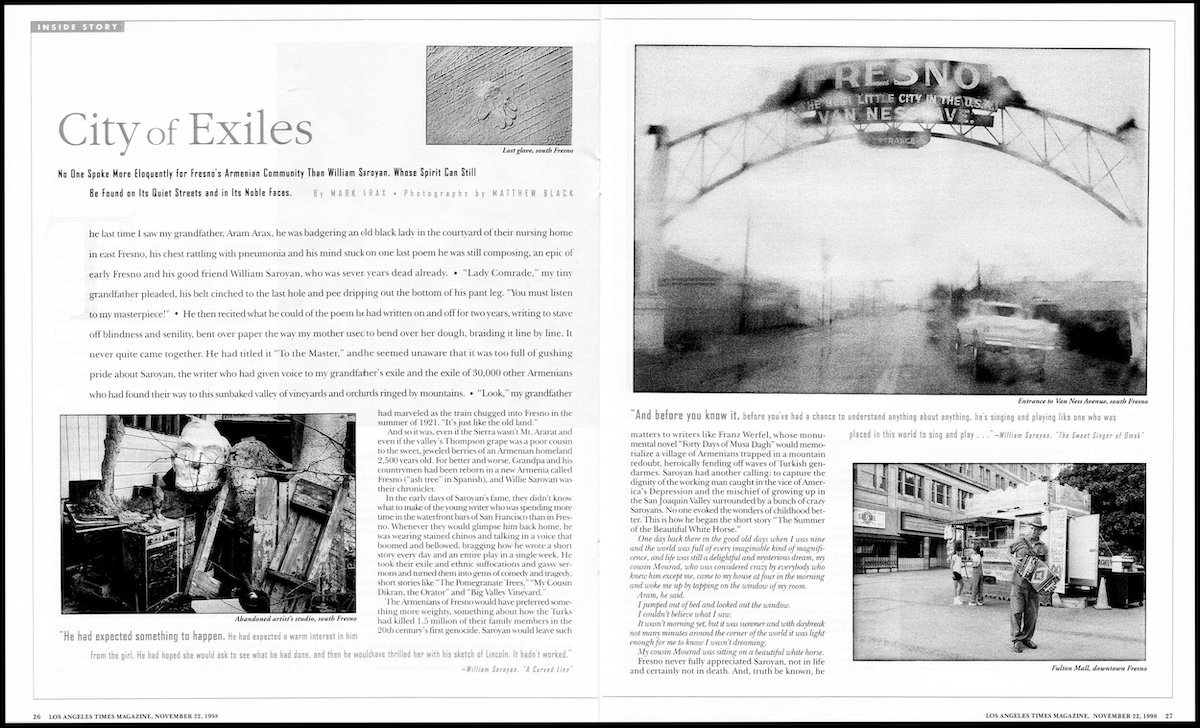

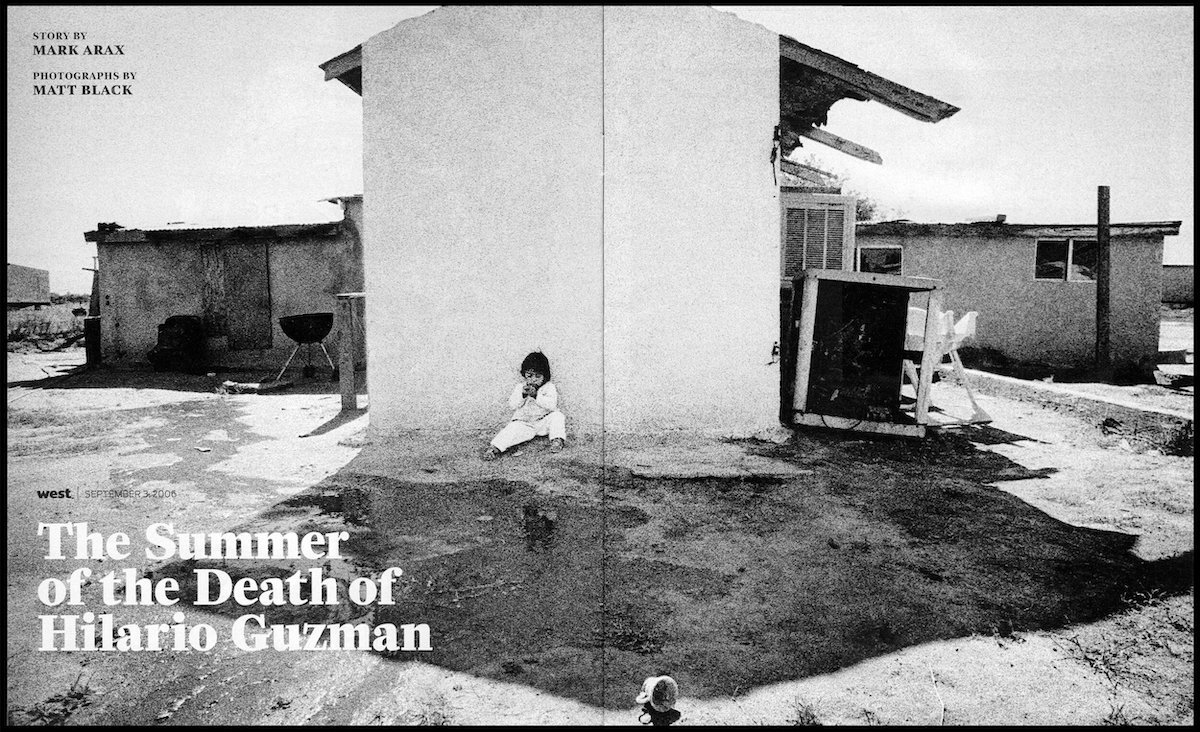

Hand in hand with the great raw output of Central Valley agriculture is the stepping stone that it has provided for generations of immigrants and migrants. Since the first US Census to include California, in 1850, the number of immigrants and migrants drawn to the state has been markedly higher than to the rest of the nation. Starting with Chinese immigrants at the Gold Rush, to Filipino, Mexican, Portuguese, Vietnamese, Armenian, and Indian populations; to Midwestern migrants during the Dust Bowl and Great Depression in the 1930s; to Hmong and Laotian immigrants after the Secret War in Laos during the Vietnam War; and most recently, to indigenous Mexicans as environmental degradation severely affected traditional corn production in the 1990s, group after group has gained an economic and social foothold in America via the Valley's fields, orchards, and groves. Today, the state is home to 11 million immigrants.

Shaping American Geography

“How many other places like mine are there in America?”

THE VALLEY (1938)

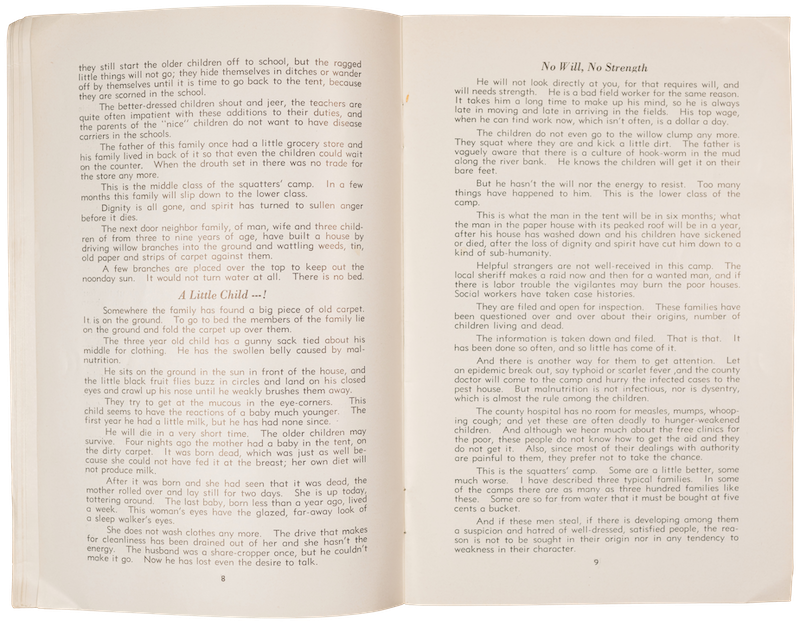

Displaced by the effects of the Dust Bowl, the Great Depression, and farming innovations that made sharecropping obsolete, nearly 500,000 Midwesterners flooded into California between 1935 and 1938. This exodus and the harsh treatment of migrants as they moved and settled in the West was documented by Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographers like Dorothea Lange, Arthur Rothstein, and Russel Lee and was written about by John Steinbeck, both in nonfiction articles published in The San Francisco News (later collected as Their Blood is Strong, then as Harvest Gypsies) and in his celebrated novel, The Grapes of Wrath.

“In this series the word ‘dignity’ has been used several times. It has been used not as some attitude of self-importance, but simply as a register of a man’s responsibility to the community […] We regard this destruction of dignity, then, as one of the most regrettable results of the migrant’s life.”

— John Steinbeck, Their Blood is Strong, Simon J. Lubin Society, San Francisco, 1938

Portraits at the Tulare migrant camp, near Visalia, California

— Arthur Rothstein, photographer, April 1940

Grape Strike and the Birth of the UFW (1965)

The United Farm Workers Union

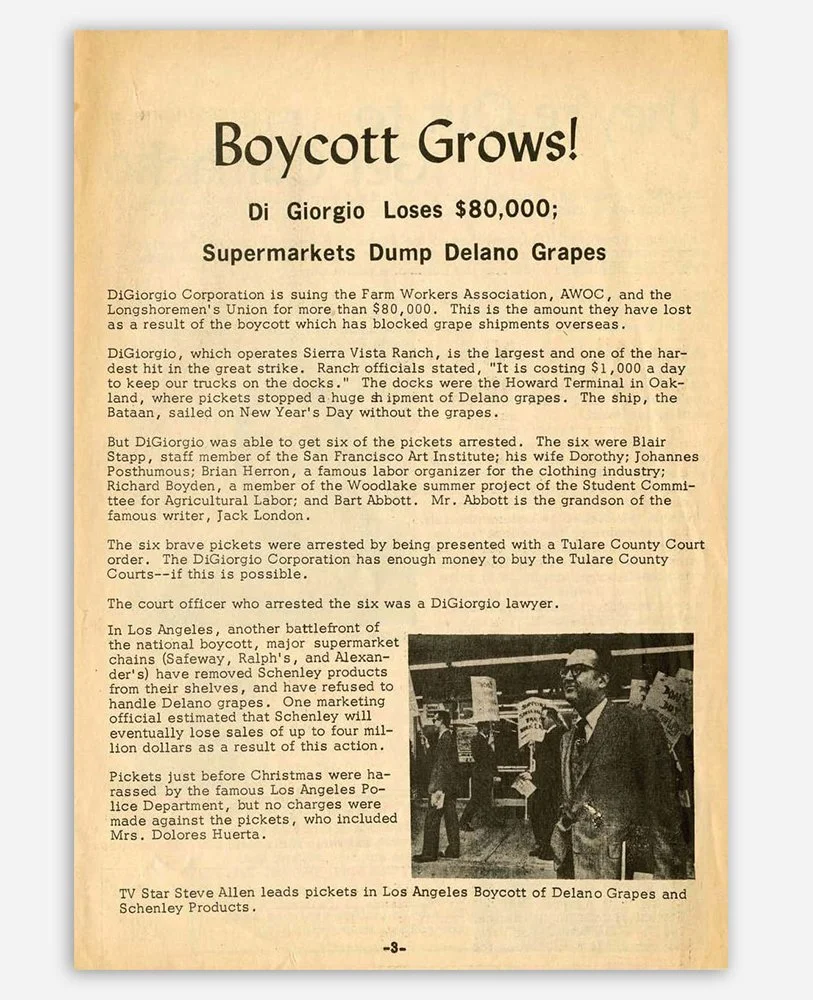

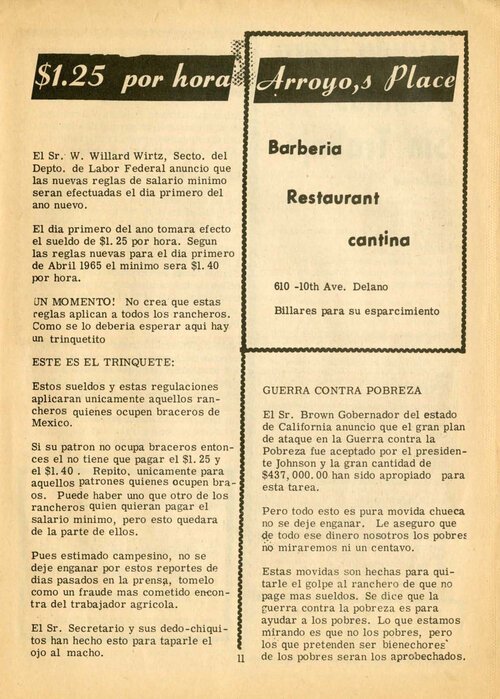

In May 1965, in the Coachella Valley of California, a grape strike led by Filipino workers of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee successfully led to higher wages. These workers, following the crops, moved north to Delano in the San Joaquin Valley, only to find they were again to be paid less than minimum wage.

In response, AWOC workers joined with Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta’s National Farmworkers Association, creating the United Farmworkers (UFW). They spent the next five years in a grassroots effort to improve working conditions for table grape pickers, beginning with a strike against grape growers, a march from Delano to Sacramento that covered over 300 miles, a grape boycott that became international in scope, and a 25-day fast by Cesar Chavez. Senator Robert F. Kennedy and thousands of people came to Delano to witness its end on Sunday, March 10, 1968.

On July 29, 1970, the union and table grape growers signed a collective bargaining agreement for wages and benefits that improved the conditions and lives of over 10,000 workers.

“Our struggle is not easy. Those who oppose our cause are rich and powerful and they have many allies in high places. We are poor. Our allies are few. But we have something the rich do not own. We have our own bodies and spirits and the justice of our cause as our weapons.”

"Fast for Life" (1988)

by Matt Black, photographer, August 1988

Delano, CA (1988)

Matt Black, Photographer, 1988

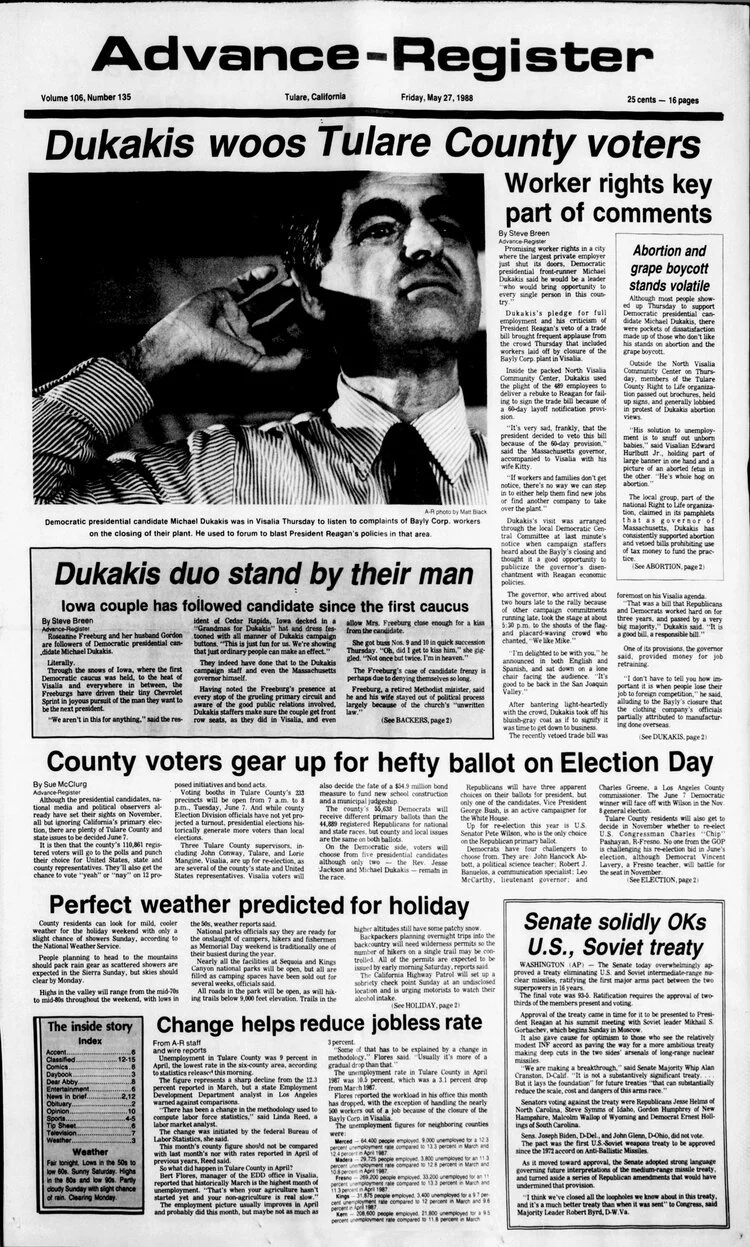

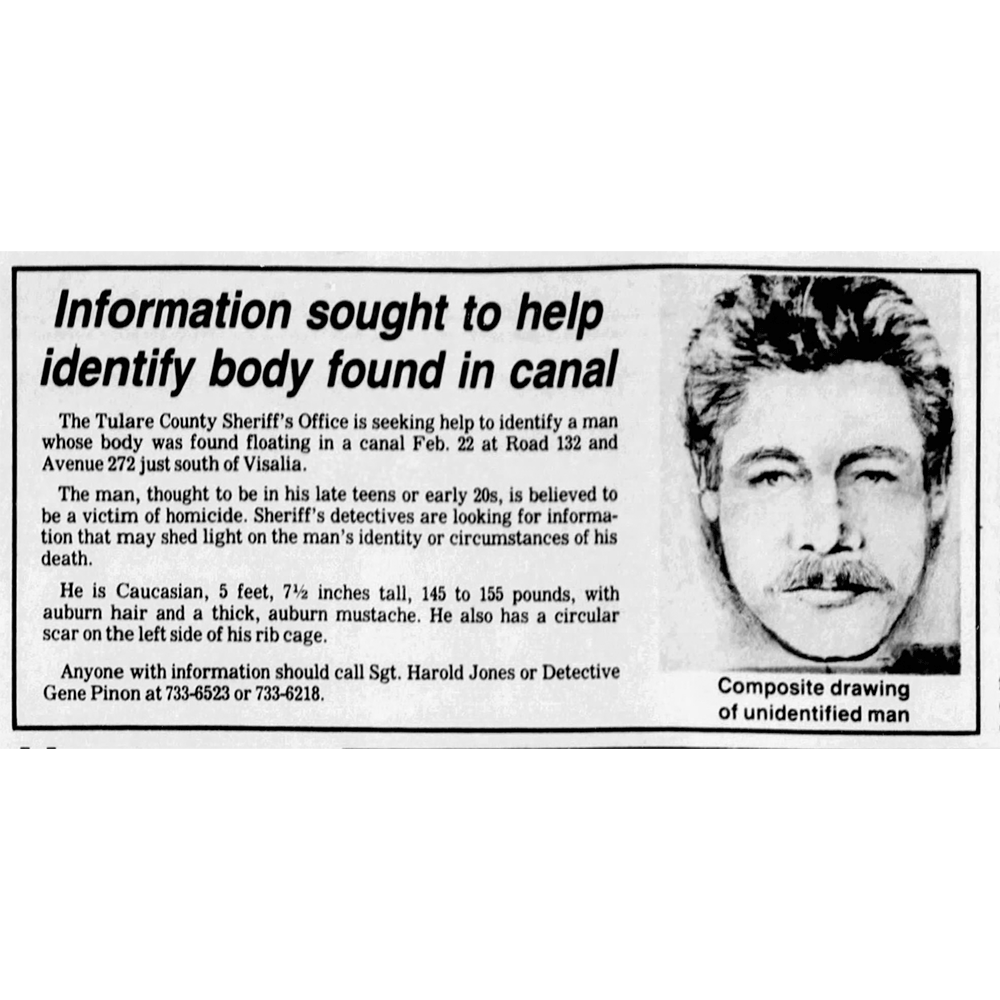

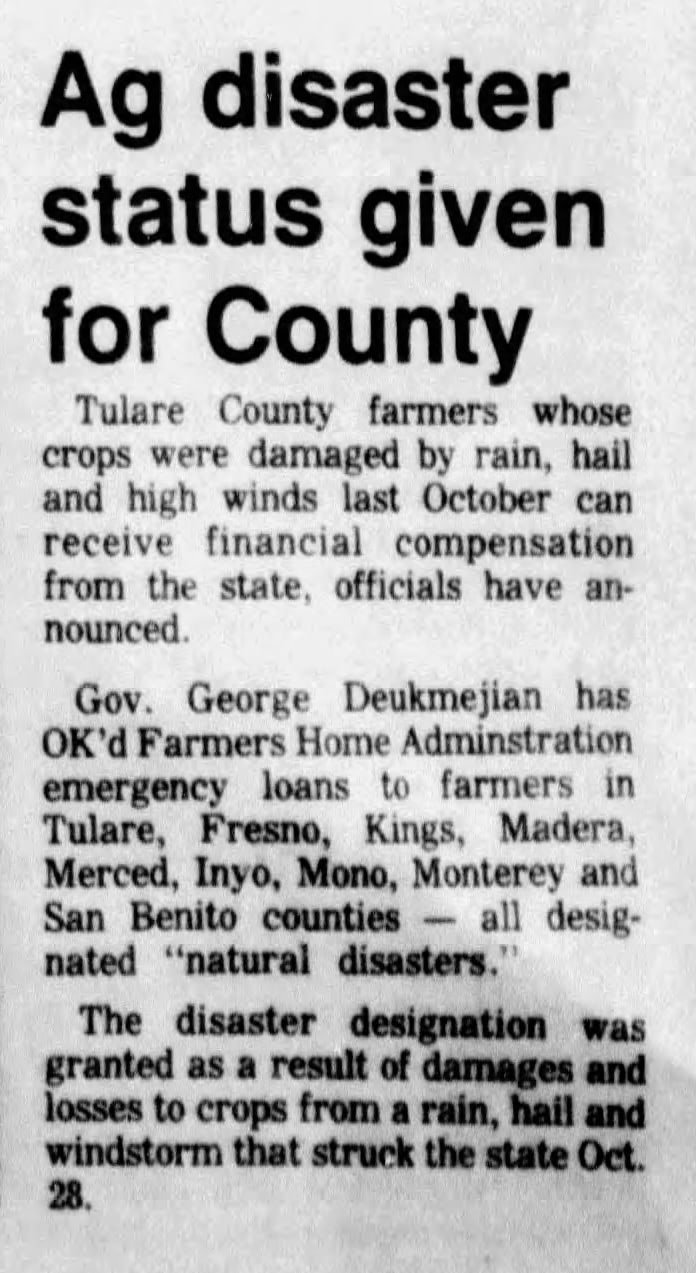

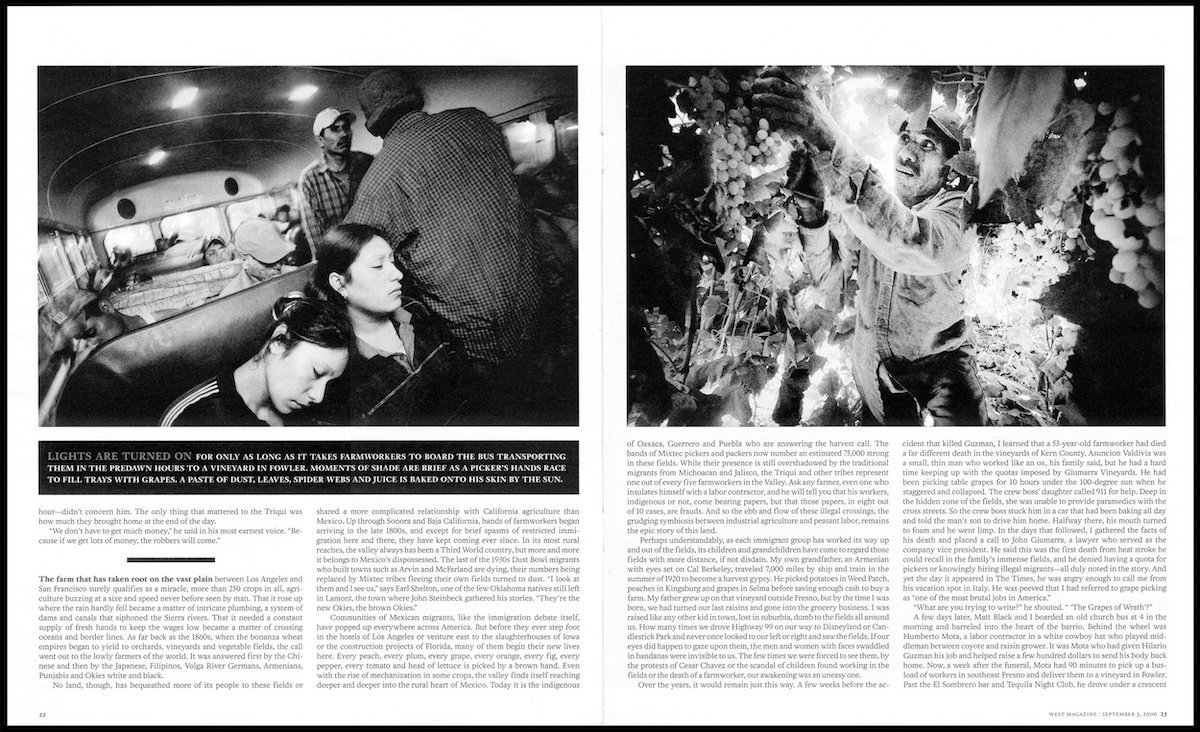

The fight for fair working and environmental conditions was far from over. In 1984, spurred by a cancer cluster in McFarland, California, which involved children, another four-year boycott of table grapes was begun by the UFW to protest agricultural pesticides in widespread use across the Central Valley and elsewhere, as well as persistent poor working conditions and lack of contracts with growers. Though many noted that the protest was smaller in scope than in 1968 and that the UFW had lost some political influence after George “Duke” Deukmejian became California governor in 1982, union members and citizens picketed supermarkets that sold grapes, and in 1988, Cesar Chavez fasted for 36 days to draw attention to the issues. For the end of the fast in Delano on August 22, 1988, Ethel Kennedy was present, as were Reverend Jesse Jackson and over 7,000 farmworkers. Matt Black, just past 18, had been hired as a photographer at The Tulare Advance-Register. Frustrated with the newspaper’s coverage of the historic grape fast, when they refused to send a staff member to cover the concluding event — instead publishing a front-page story quoting a local farmer calling Chavez a “fraud” — Black photographed the end of Chavez’s fast unassigned.

Matt Black Central Valley Journalism (1987-2021)

United Farm Workers Union (2021)

Today, the “fight in the fields” is not yet over. In the summer of 2021, the UFW worked to protect farmworkers across the Pacific Northwest during an unprecedented heat wave that killed hundreds:

“For Farmworkers, Heat Too Often Means Needless Death,” Inside Climate News, July 9, 2021

“The United Farm Workers and Oregon-based Pineros y Campesinos Unidos del Noroeste (PCUN) urged state officials to issue emergency rules to protect agricultural workers from unsafe conditions during heat waves.

“And on Tuesday, Gov. Kate Brown directed Oregon Occupational Safety and Health officials to do just that, temporarily expanding requirements for employers to provide shade, rest periods and cool water during heat waves until permanent rules are put in place.”

The Central Valley encompasses all or parts of 19 California counties. Their total value of agricultural production in 2019 is as follows:

Butte County: $650,982,000

Colusa County: $924,963,000

Glenn County: $855,612,000

Fresno County: $7,714,540,000

Kern County: $7,692,667,000

Kings County: $2,187,693,000

Madera County: $1,998,826,000

Merced County: $3,270,959,000

Placer County: $80,714,000

San Joaquin County: $2,638,145,000

Sacramento County: $60,385,000

Shasta County: $79,547,000

Solano County: $372,113,000

Stanislaus County: $3,526,856,000

Sutter County: $26,292,000

Tehama County: $99,642,000

Tulare County: $7,508,852,000

Yolo County: $708,329,000

Yuba County: $231,990,000

$40,629,107,000